Scanniclift Copse Mines

- Teign Mine -

By Andrew Westcott

Back To Mining Introduction > Location 1

The workings I'll be dealing with here are the adits associated with Teign Mine which can be found in Scanniclift Copse to the South-West of the parish of Doddiscombsleigh. I've indicated the location on my map on the 'Mining Introduction' page, and they can be found at Ordnance Survey coordinates SX 844 863. Scanniclift Copse is managed by the Devon Wildlife Trust, and is situated on one side of a steep-sided valley adjacent to the River Teign, and paths and steps have been created within the woodland to aid access for visitors and to try to discourage people from wandering off the main route.

These woods are an excellent place to see the natural flora, and occasionally the fauna, of the area, and there is a good representation of woodland plant species to be seen; any fallen trees, and there are many in this wood, are left in situ to enhance the habitat. Bluebells are particularly prolific in this wood, and a well-timed visit will reward the visitor with a blue haze of the flowers on the woodland floor. But despite the many wonders of this place, it is for the moment the mining history I'm interested in.

At several points along the constructed pathways it is possible to see depressions in the ground where exploratory excavations may have taken place as the prospectors searched for manganese ore deposits near the surface, but presumably were fairly quickly abandoned as there is rather little in the way of spoil heaps adjacent to these depressions. The geology of this particular area is especially interesting as the woods sit on a region where an intrusive plug of igneous rock meets the sedimentary, and as a result there is evidence of the effects of metamorphosis on the shales and chert in this vicinity, and the igneous rock itself is apparent at the surface within these woods in a small location at the higher Western end.

Photo 1

Scanniclift CopseScanniclift Copse, on the hill overlooking the river teign

The part of this woodland of greatest interest to me, however, is a small section at the higher Eastern end which is visible in photo 1 as the section jutting out at the top left. This section of the copse was until recently privately owned, but is now in the care of the Devon Wildlife Trust, as is much of the rest of the wood. Here there is evidence of ore extraction with considerable spoil heaps adjacent to several adits, at least one at an upper level and another two occurring at lower locations, one of which appears to drain the complex as water emanates from it.

Both of the two lower adits open out onto an old overgrown track passing through the upper part of Scanniclift Copse, and presumably this was how the ore was removed from the area; it is unknown for now in which direction it would have been sent, but I strongly suspect it was taken, via Woodah farm, to a large open cast working for processing, this area dealt with as lake Farm Quarry, mining area 2.

Much of the manganese ore occurred close to the surface and as a result, the access tunnels and some stopings have collapsed, the entrances to the original adits having also fallen in although their location can be easily determined upon examination of the area.

Photo 2

One of the two lower aditsCollapsed entrance to one of the 2 adits on the lower level, which open out onto the track

It is difficult to determine an age for these workings, but allowing for the time required for the workings to fall into ruin and become overgrown, an initial estimate based on these criteria alone would indicate the latter part of the 1700s to early 1800s as a possible period of industrial activity. In support of this, there is mention that originally one of the chief producers of manganese ore in Devon was the mine in Upton Pyne which ran from 1788 until 1823, but when the ore deposits had become exhausted the focus for manganese ore production moved to the Teign Valley area. Although there are small manganese workings near Ashton, I am at the moment assuming that most of the ore was extracted at Scanniclift and Lake Farm Quarry, and the date for the closure of the Upton Pyne mine gives us, at least, a possible date for when these mines could have been operational.

When driving an adit into a hillside, it was usual practice for the miners to initially cut a level channel or gully into the hill, in order to expose a sufficient height of rock face to safely support a tunnelling operation with minimal risk of collapse. The two lower adits can be seen to have followed this style, but they are now in a very poor state of preservation, as the entrances have collapsed, and the sides of the cut and material from above the tunnel entrance has fallen inwards to completely block access.

Photo 2 shows one of the original adit entrances at the lower level and as can be seen, it is in a very poor condition and it appears that the tunnel has collapsed for a short distance of its route. This particular adit is completely dry with no evidence of it ever having been used for drainage; sufficient material has fallen into the cut to completely block the mine entrance but the original rocky sides of the cut are still visible. There is a fairly large spoil heap near the mouth of this adit on the opposite side of the track onto which it opens.

Photo 3

Lower drainage aditcollapsed entrance of the second of the 2 lower adits which open out onto the track, with water draining out

Photo 3 shows the site of the other lower adit, also opening out onto the old track with a reasonably sized spoil heap on the opposite side of the track. Despite this adit appearing in even worse condition than the previous one, I believe this adit itself to be generally intact as there is no evidence of sunken ground above it, although it is inaccessible from this side due to the rubble and earth blocking its entrance, much of it appearing to have originated from the spoil heaps further up on the hillside. The uprooting of a large oak which was growing in the cut has also complicated matters somewhat.

The substantial spoil heaps by this adit suggest much use, and a fair amount of water is running out from it indicating it functioned as the drainage adit for the whole complex. Incidentally, whilst poking around under rocks like you do, I noticed the presence of frogs living under some of the larger water-bound rocks. This location is some distance from any other body of water making me wonder just how the first frog to colonise this area arrived, and as it is essentially an isolated habitat, whether these frogs now differ from the regular population to any degree. Perhaps someone suitably knowledgeable in the study of amphibians may be interested in studying them.

The remains of a stone built structure can be seen next to the lower drainage adit, although it is little more now than a broken rectangle of stones which can be difficult to identify unless you happen to be standing at the correct location. Identifying it is far easier in the Winter, which is the only time the undergrowth has died back sufficiently to render the base of the walls visible.

|

|

Photo 4 shows the base of a stone wall, and photo 5 shows what would have been the floor of the building from further back. This building could possibly have been used as a workshop for maintaining tools and producing timber for use underground, and may have doubled up as a mine office and temporary dwelling or rest room; whatever it's use, it was considered important enough to be built from stone rather than just timber.

A quick look over any of the spoil heaps will soon reveal pieces of manganese ore which, despite the difficulty the miners must have experienced in blasting and hacking the ore from the country rock, have been discarded along with the waste although most pieces are small, impure and attached to larger pieces of waste rock. I can only assume these occasional pieces of ore were too impure to have any value.

|

|

Photo 6 shows a sample of a piece of low-grade manganese ore. The manganese ore itself can easily be identified as weathered samples take on an almost purple-brown appearance under the green canopy of the trees and when a sample is broken to reveal a fresh face it displays a blue-grey colour with an almost sub-metallic lustre. Photo 7 shows an unusual rock sample which appears to be a type of vesicular basalt, examples of which can be found scattered around the area; presumably the occurrence of such a rock type is related to there having been a large body of intrusive molten magma so close by.

Photo 8

Stope at the surfaceWhere a stope has reached the surface, leaving an opening known as a gunnis

Further up the hill is evidence of a lot more activity, representing what I like to refer to as the upper levels. I imagine there must be quite a network of tunnels and cavities under this part of the woods with large areas hollowed out as the ore, which tended to occur in large irregular bodies rather than thin seams, was removed. There are some areas where the stoping activities of the miners reached the surface, the hole remaining being known as a gunnis; one such place is shown in photo 8.

This particular site is obviously where the miners intentionally broke the surface in the quest for the manganese ore, and the resulting hole probably also served to help ventilation. The miners sensibly left a small bridge of rock in place here to help support the mass of rock to the left of the picture, which would otherwise have been liable to collapse. There is no access to the workings through this opening now, as rubble has fallen in and blocked it at the bottom.

Photo 9

Upper adit entranceThe collapsed upper adit entrance, leading to some major excavations

The ground in this higher area has been so disturbed by the mining operation and later collapses that it is difficult to determine exactly how many adits were originally here, but two separate spoil heaps can easily be identified and as this mine was probably worked over a period extending to several decades, worked out parts would have been abandoned and waste rock dumped in the area leading to the apparently confused state visible now.

Photo 9 shows a positively identifiable adit entrance, the oak tree growing there lending weight to the considerable age of this mine. The original sides of the cut are easily visible here, although there is the inevitable build up of debris within the entrance caused when the tunnel fell in.

If you walk into this old adit entrance and follow the path it would have taken when underground, it appears that the whole mine has collapsed to form a deep gorge with vertical rock faces, with the floor strewn with large boulders, fallen trees and broken branches. If you climb over these boulders which were presumably once the roof of this part of the workings, and fight your way onwards through the jungle of undergrowth you will be greeted with a yawning opening about 15 feet high set in a near-vertical rock face.

This opening leads to the remaining intact part of this upper level; the entrance is partially filled by rubble which fell when the roof of the earlier part of the mine collapsed, this having been added to by rubbish being dumped in over from the field above in years gone by. This accumulation of debris means that to enter, you need to climb down over it, a slope of around 30 to 40 degrees. This opening was, I believe, once fairly deep into the mine and it is only the collapse of the area further back which has exposed it.

|

|

Photo 10 shows the vast area, described earlier, which must have once been a large underground gallery, now collapsed. Note the large boulders scattered around, once part of the roof.

Photo 11 shows the entrance to the remaining intact part of the upper level, located at the furthest point from the original adit entrance. It appears that the massive collapse happened a long time ago judging by the lichen and vegetation growing on the rocks, but that doesn't mean it's safe to enter; "hanging death" is a mine explorer's term for large pieces of rock which could fall from the roof without warning.

Back to top

Exploring The Workings

Photo 12

Looking into the top aditLooking into the intact part of the mine. The size of the cavity is impressive, as can be judged by the large ferns

The following section deals exclusively with the underground aspects of this, the only remaining accessible part of the complex. Currently the only way in is through this large opening, and to try to demonstrate the size of the cavity I have included a picture of it here as photo 12, the large ferns on the inside giving some idea of scale. I am always cautious about entering old workings like this, and strongly recommend you don't do it unless you have at least some experience of entering such places. It is sensible to ensure you have adequate and reliable lighting, a bump hat to protect your head against possible minor rock falls, and additional company, some of whom should remain outside just in case the worst happens, as even if you have informed others of your intentions it could still be extremely difficult for a rescue party to locate the actual part of the mine involved.

In the case of this adit, I examined the entrance for evidence of instability, but the floor was green with moss and the rock of the roof was covered in lichens, indicating nothing had moved for decades, so I deemed it reasonably safe to enter. The contrast between the hot humidity of the woods and the cool of the mine was striking as I climbed down over the rubble at the entrance, and looking up, the stoping could be easily seen extending in an arc overhead as the miners had followed the path of the ore body. The chamber at this point is perhaps 10 feet wide and around 15 feet high indicating a substantial amount of ore must have been extracted here.

Photo 13

Interior of the upper aditThe interior of the adit, taken using ambient light and a long exposure time

It is possible to continue on foot for about a hundred feet before coming to what initially appears to be the end of the workings, and from this point I took a photo to show the interior of this section of the mine which I have reproduced here as photo 13. This image was taken using the very small amount of natural light which had made it this far into the mine, and the exposure for this required a full 2 minutes to produce the result seen here.

The interesting aspect for me is that this image shows the true daylight colours of the rocks, and in the high resolution image pieces of purple-blue manganese ore can be seen on the floor and walls along with the orange staining of iron deposits. The floor is strewn with loose rocks, and my first thought was that part of the roof had collapsed, but it became apparent that this was in fact waste rock which had been piled up, mainly in order to avoid the task of removing it, but with the added benefit of raising the floor, by so doing presumably reducing the height of the timber scaffolding required to reach the top of the stoping.

Initially, I was unable to discover any evidence of tool marks on the walls of this chamber, making me wonder just how the rock was broken. The ore itself is fairly soft and a pick would have succeeded in getting the job done, but the much harder surrounding rock is another matter entirely as these workings pre-date the invention of Dynamite, (invented by Alfred Nobel and patented in 1867) and only black powder explosive would have been available to the miners of the day. In order to blast the rock, deep holes would need to be drilled into the rock in order to place the explosive charge, and a further search did in fact reveal evidence of the remains of two such shot holes.

This cavity initially appears to be the limit to how far the workings progressed underground, but in fact they do continue on for some considerable distance although access is through a rather small gap at the rear left hand side of this chamber followed by a drop of about nine feet before another large chamber presents itself. Many years ago I remember shining a powerful lamp into this hole and seeing timbers lying around and considering how far into the mine this was, these timbers can only be the remains of the original scaffolding used by the miners all those years ago.

Exploring this deeper section would involve climbing equipment and people rather younger and more experienced than myself, and of course permission must be sought from the landowner before such a visit is attempted; unfortunately I may now a bit long in the tooth for such a venture, but I'd be an enthusiastic hanger-on if anyone decides to arrange a visit!

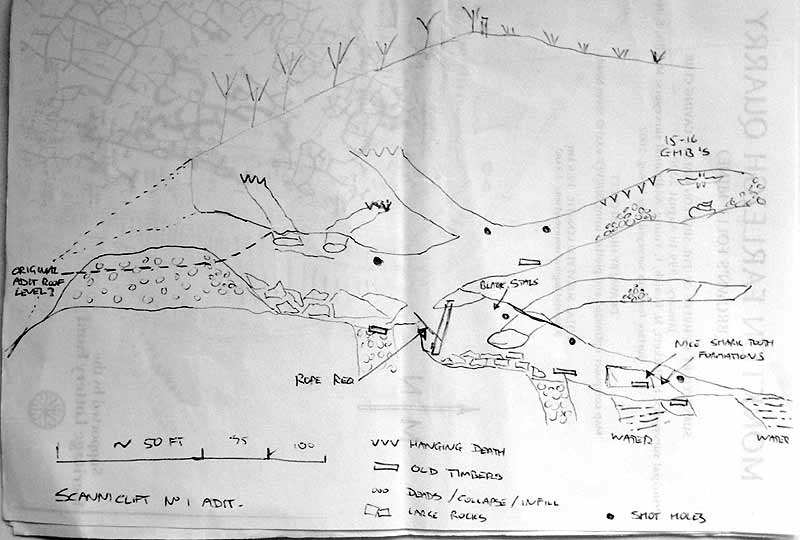

A good while ago I was contacted by someone who ventured into the deeper sections of this mine and he made several interesting observations and drew a sketch of the interior, reproduced below. Unfortunately, due to the passage of time and the demise of various computers, the information has been lost along with the identity of the person who drew the diagram, so I can't give the appropriate credit. If it was you, please get in touch!

Back to top

I can be contacted at this address:

Copyright © Andrew Westcott 2003 - 2025

I'm happy for anyone to use this material for private, non-commercial or educational purposes, but credit to the author must be given. For any other use please contact me for permission.