|

|

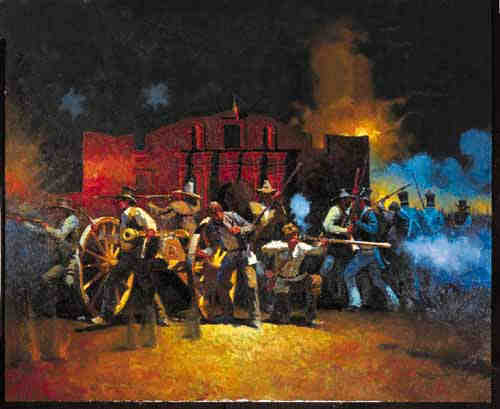

Patriotism is a subject rarely discussed in March. It is usually reserved for Fourth of July celebrations and Veterans Day Parades. But for some, March 6th is a day to pause and reflect, for it is the anniversary of one of the most glorified battles ever waged by humankind.

The battle of the Alamo conjures up images of Davy Crockett's coonskin cap and Jim Bowie's famous Bowie knife. Everyone is familiar with the famous rallying cry, "Remember the Alamo!" But how many people honestly know what the battle was about? Who fought it? Or even who won?

The story of the Alamo is one that has been passed down through the years, embellished by generation after generation, until history and legend have become nearly indistinguishable. At times, it takes on the flavor of a tall tale, but in reality we know that things are not always as they seem. Heroes are not always so heroic...selfless sacrifice is not always so selfless. But more often than not, the truth is infinitely more fascinating than the myth.

In 1836, the Alamo was the setting for the

first major military conflict in the battle

for Texas independence. It was a revolution,

not unlike the American Revolution just sixty

years before. Mexicans and Americans alike

had settled the Texas territory with the

security of a Mexican constitution and the

promise of land to call their own. But

everything changed with the rise of Antonio

Lopez de Santa Anna as President of Mexico.

He quickly transformed the Presidency into a

dictatorship, abolished the constitution of

1824, and reneged on the land deals offered

by the former Mexican government. And just

as quickly, the Texans began to show their

disapproval.

In 1836, the Alamo was the setting for the

first major military conflict in the battle

for Texas independence. It was a revolution,

not unlike the American Revolution just sixty

years before. Mexicans and Americans alike

had settled the Texas territory with the

security of a Mexican constitution and the

promise of land to call their own. But

everything changed with the rise of Antonio

Lopez de Santa Anna as President of Mexico.

He quickly transformed the Presidency into a

dictatorship, abolished the constitution of

1824, and reneged on the land deals offered

by the former Mexican government. And just

as quickly, the Texans began to show their

disapproval.

There are many misconceptions about the Alamo, the first of which is the belief that the Alamo itself was a fortress. It was not. It was a church, a mission long-abandoned by the Spanish before the earlier Mexican revolution against Spain. Another popular belief was that Texas soldiers were sent to defend this post at San Antonio. The truth is, they were sent to evacuate and dismantle it so that the Mexican forces could not use it as a base of operations inside the boundaries of Texas.

But perhaps the saddest misconception of all is the idea that the legendary figures Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie were the major players in the battle of the Alamo. Perhaps it is because the two had already made a name for themselves before they entered the Alamo walls which earned them that status. But the fact is, the two played a relatively small role in comparison to that of a much more obscure hero.

Davy Crockett was a legend even in his own

time. A Tennessee mountaineer, Crockett was

probably most famous as an Indian fighter.

Although relatively uneducated, his

folklorish popularity had even earned him a

seat in the United States Senate. But when

he lost his bid for re-election, the aging

mountaineer went in search of a cause to

fight for, perhaps to reclaim some of the

glory of his youth. "You can all go to

hell," Crockett said after the loss. "I'm

going to Texas." He and sixteen of his

"Tennessee Boys" volunteered their services

to defend the post at San Antonio. Although

an important historical figure, Crockett

asked for no more (and in fact, would accept

no more) than the rank of First Private at

the Alamo. He was there to fight for the

liberation of Texas. Nothing more.

Davy Crockett was a legend even in his own

time. A Tennessee mountaineer, Crockett was

probably most famous as an Indian fighter.

Although relatively uneducated, his

folklorish popularity had even earned him a

seat in the United States Senate. But when

he lost his bid for re-election, the aging

mountaineer went in search of a cause to

fight for, perhaps to reclaim some of the

glory of his youth. "You can all go to

hell," Crockett said after the loss. "I'm

going to Texas." He and sixteen of his

"Tennessee Boys" volunteered their services

to defend the post at San Antonio. Although

an important historical figure, Crockett

asked for no more (and in fact, would accept

no more) than the rank of First Private at

the Alamo. He was there to fight for the

liberation of Texas. Nothing more.

Colonel Jim Bowie was also a legendary figure

of the time, popularly considered to be the

most dangerous man alive. And although he

was in command of the Alamo at the beginning

of the siege, he (like Crockett) was an aging

legend. An injury two days into the siege,

compounded by an illness that had plagued him

for weeks, forced him to concede his command

to the young William Barret Travis. He spent

the last eleven days of the thirteen-day

siege on his death bed.

Colonel Jim Bowie was also a legendary figure

of the time, popularly considered to be the

most dangerous man alive. And although he

was in command of the Alamo at the beginning

of the siege, he (like Crockett) was an aging

legend. An injury two days into the siege,

compounded by an illness that had plagued him

for weeks, forced him to concede his command

to the young William Barret Travis. He spent

the last eleven days of the thirteen-day

siege on his death bed.

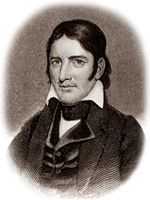

It was William Travis, the 26-year-old

cavalry Colonel from South Carolina, who

stood to face an army with a meager 187

volunteers. Except for a handful of men who

had arrived with Travis and Bowie, the

majority of the Alamo defenders were not

professional soldiers. They were San Antonio

citizens, both Mexican and American, farmers

who stayed to defend the land they had worked

so hard to call their own.

It was William Travis, the 26-year-old

cavalry Colonel from South Carolina, who

stood to face an army with a meager 187

volunteers. Except for a handful of men who

had arrived with Travis and Bowie, the

majority of the Alamo defenders were not

professional soldiers. They were San Antonio

citizens, both Mexican and American, farmers

who stayed to defend the land they had worked

so hard to call their own.

It was Travis, with these 187 men, who performed nothing less than a miracle. Knowing that the Independence Convention was underway and that Texas needed time to raise an army, Travis had to hold Santa Anna off as long as possible. Santa Anna could have ignored this handful of revolutionaries altogether, marched right past them and caught the Texans off guard before they could organize themselves. Instead, he played right into Travis' hands, devoting four thousand soldiers and thirteen days to the defeat of the Texans inside the Alamo.

And it is Travis' letters, above all else, that give us our only first-hand glimpse inside the fortress during those thirteen days. Through him, we see the hope, the futility, and the blind determination of a group of men who stood and died for something they believed in.

Many of the letters were requests for aid that never came. On the second day of the siege, Travis wrote what would become the most famous of the Alamo letters:

"To the people of Texas and all Americans in the world --Fellow Citizens and Compatriots

I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna - I have sustained a continual bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man - The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if this fort is taken - I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls - I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American Character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch -- The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due his own honor & that of his country -

Victory or Death.

William Barret Travis"

As the days dragged on and the enemy forces grew, Travis knew that the end was near. By the tenth day of the siege, although angry that his calls for assistance had gone unheeded, his pride in his men and determination for their cause had not faltered. In a letter addressed to the Independence Convention, he wrote:

"...I feel confident that the determined valour and desperate courage heretofore envinced by my men will not fail them in the last struggle. And although they may be sacrificed to the vengeance of a Gothic enemy, the victory will cost the enemy so dear, that it will be worse for him than a defeat..."

By the twelfth day, Travis knew that time was running out. That Saturday evening, as the sun began to set, he stood before the tired group of Texans who had gathered in the courtyard of the Alamo chapel.

William Barret Travis drew his sword from his sheath, drew a line in the sand with its tip, and offered his men a final choice. He offered them the chance to escape the fortress before it was too late, with the promise that they would go with his blessing. A single Frenchman took him up on the offer, and Travis was true to his word. With a handshake, Travis bid him safe passage through the enemy lines.

Then he turned back to the rest of his men. "Those of you prepared to give their lives in freedom's cause, come over to me."

Every last man but for one crossed the line that day, including the ailing Jim Bowie who asked that his cot be carried across. Every last man would lie dead somewhere in the compound by the dawn of the next day, but that night they took their rightful place as some of the most courageous freedom fighters in the course of human history.

Travis had been right. Texas had declared its independence and Sam Houston had begun to raise an army by the time the Alamo finally fell. The 187 defenders had not lived to see it, but they had insured Santa Anna's defeat later at San Jacinto by giving Texas what it needed most -- time.

He had also been right about the "last struggle" of his men. In the pre-dawn hours of Sunday, March 6th, the Mexican army began scaling the high stone walls of the Alamo. Colonel Travis himself was one of the first to physically engage the enemy. And Travis himself was one of the first to die.

The bloody battle that ensued would last for little more than an hour, and not one man who stood to defend the Alamo would live to tell the tale. But those 187 volunteers took over 600 Mexican soldiers with them that morning, making it a costly victory for Santa Anna, indeed. For in addition to the loss of his men, in his blind determination to take the Alamo, Santa Anna lost Texas.

William Barret Travis left behind a detailed record of heroes in the making. But as a divorced father of a three-year-old son, he also left us a poignant reminder of the human cost of war.

"Take care of my little boy," he wrote a friend in the last days of the siege. "If the country should be saved, I may make for him a splendid fortune. But if the country should be lost and I should perish, he will have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country."

At times, history can elevate a group of

people to a level of heroism that no human

being could possibly attain. But in the case

of the Alamo defenders, it was their

irrepressible spirit which brought them to

that level. History merely documented the

facts.