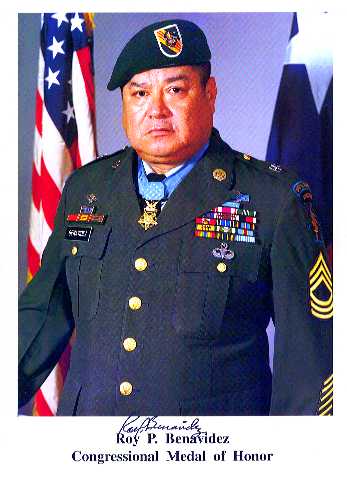

BENAVIDEZ, ROY P.

Rank and Organization: Master Sergeant. Detachment B-56, 5th Special Forces Group, Republic of Vietnam

Place and Date: West of Loc Ninh on 2 May 1968

Entered Service at: Houston, Texas June 1955

Date and Place of Birth: 5 August 1935, DeWitt County, Cuero, Texas

Citation:

Master Sergeant, then Staff Sergeant, United States Army. Who distinguished himself by a series of daring and extremely glorious actions on 2 May 1968 while assigned to Detachment B-56, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne). 1st Special Forces, Republic of Vietnam. On the morning of 2 May 1968, a 12-man Special Forces Reconnaissance Team was inserted by helicopters in a dense jungle area west of Loc Ninh, Vietnam to gather intelligence information about confirmed large-scale enemy activity. This area was controlled and routinely patrolled by the North Vietnamese Army. After a short period of time on the ground, the team met heavy enemy resistance and requested emergency extraction. 3 helicopters attempted extraction, but were unable to land due to intense enemy small arms and anti-aircraft fire. Sergeant Benavidez was at the Forward Operating Base in Loc Ninh monitoring the operation by radio when these helicopters returned to off-load wounded crew members and to assess aircraft damage. Sergeant Benavidez voluntarily boarded a returning aircraft to assist in another extraction attempt. Realizing that all the team members were either dead or wounded and unable to move to the pickup zone, he directed the aircraft to a nearby clearing where he jumped from the hovering helicopter, and ran approximately 75 meters under withering small arms fire to the crippled team. Prior to reaching the team's position he was wounded in his right leg, face and head. Despite these painful injuries he took charge, repositioning the team members and directing their fire to facilitate the landing of an extraction aircraft, and the loading of wounded and dead team members. He then threw smoke canisters to direct the aircraft to the team's position. Despite his severe wounds and under intense enemy fire, he carried and dragged half of the wounded team members to the awaiting aircraft. He then provided protective fire by running alongside the aircraft as it moved to pick up the remaining team members. As the enemy's fire intensified, he hurried to recover the body and classified documents on the dead team leader. When he reached the leader's body, Sergeant Benavidez was severely wounded by small arms fire in the abdomen and grenade fragments in his back. At nearly the same moment, the aircraft pilot was mortally wounded, and his helicopter crashed. Although in extremely critical condition due to his multiple wounds, Sergeant Benavidez secured the classified documents and made his way back to the wreckage, where he aided the wounded out of the overturned aircraft, and gathered the stunned survivors into a defensive perimeter. Under increasing enemy automatic weapons and grenade fire, he moved around the perimeter distributing water and ammunition to his weary men, reinstilling in them a will to live and fight. Facing a buildup of enemy opposition with a beleaguered team, Sergeant Benavidez mustered his strength, began calling in tactical air strikes and directed the fire from supporting gun ships to suppress the enemy's fire and so permit another extraction attempt. He was wounded again in his thigh by small arms fire while administering first aid to a wounded team member just before another extraction helicopter was able to land. His indomitable spirit kept him going as he began to ferry his comrades to the craft. On his second trip with the wounded, he was clubbed with additional wounds to his head and arms before killing his adversary. He then continued under devastating fire to carry the wounded to the helicopter. Upon reaching the aircraft, he spotted and killed 2 enemy soldiers who were rushing the craft from an angle that prevented the aircraft door gunner from firing upon them. With little strength remaining, he made one last trip to the perimeter to ensure that all classified material had been collected or destroyed, and to bring in the remaining wounded. Only then, in extremely serious condition from numerous wounds and loss of blood, did he allow himself to be pulled into the extraction aircraft. Sergeant Benavidez' gallant choice to voluntarily join his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to withering enemy fire, and his refusal to be stopped despite numerous severe wounds, saved the lives of at least 8 men. His fearless personal leadership, tenacious devotion to duty, and extremely valorous actions in the face of overwhelming odds were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army.

NAVY NAMES NEW ROLL-ON/ROLL-OFF SHIP FOR U.S. ARMY HERO

15 September 2000

Secretary of the Navy Richard Danzig has announced that the Navy will honor a U.S. Army soldier awarded the nation's highest military award, the Medal of Honor, by naming the seventh in the Bob Hope class of large, medium speed, roll-on/roll-off sealift (LMSR) ships after the soldier.

The name Danzig assigned, the USNS Benavidez (T-AKR 306), honors Army Master Sgt. (then Staff Sgt.) Roy Benavidez, born Aug. 5, 1935, in Lindenau, Texas. Benavides distinguished himself in a series of daring and extremely valorous actions while assigned to Detachment B56, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, Republic of Vietnam.

On May 2, 1968, Benavidez voluntarily lead the emergency extraction of a 12-man special forces reconnaissance team that met heavy enemy resistance while gathering intelligence in an area controlled and routinely patrolled by the North Vietnamese Army. During numerous rescue attempts in which he physically carried wounded members to helicopters, he was critically wounded but continued to lead the team and gather survivors into a defensive perimeter. He distributed water and ammunition, administered to the wounded and provided protective fire as team members were picked up. During this rescue operation he safeguarded classified documents carried by the team. Benavidez' gallant choice to join his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to heavy enemy fire and his refusal to be stopped despite severe wounds, saved the lives of at least eight men.

Benavidez was first awarded the Distinguished Service Cross from Gen. William Westmoreland for his heroism. When the full story of his daring and extremely valorous actions became known, the medal was upgraded to the Medal of Honor. Former President Ronald Reagan awarded him with the Army's highest medal in 1981. Retired Master Sgt. Benavidez died Nov. 28, 1998, in San Antonio, Texas.

"Our Bob Hope class of ships are resolute assets that are always quietly there in the background. They are capable of coming forward in a vital way when America calls for reinforcement of its combat needs around the world," said Danzig. "Roy Benavidez personified that same spirit throughout his life, and most powerfully during a single action that saved lives in combat. I am delighted to have the opportunity to preserve his legacy by naming T-AKR 306 the USNS Benavidez."

"Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez was a true American hero, rising from humble origins in South Texas to become an Army legend. Wounded over 40 times as he saved the lives of eight fellow soldiers under heavy fire in Vietnam, he always said he was only doing his duty to his fellow soldiers and to the country he loved. The Navy's recognition of his selfless service is truly an appropriate tribute to Master Sgt. Benavidez's memory, and to the ideals of our nation that he epitomized," said Secretary of the Army Louis Caldera.

The USNS Benavidez is a non-combatant vessel built by Litton-Avondale Industries in New Orleans, La. The launching/christening ceremony is scheduled for next summer. The ship will be crewed by civilian mariners and operated by the U.S. Navy's Military Sealift Command, Washington, D.C. The LMSR ships are ideal for loading U.S. military combat equipment and combat support equipment needed overseas and for re-supplying military services with necessary equipment and supplies during national crisis. The ship's six-deck interior has a cargo carrying capacity of approximately 390,000 square feet and its roll-on/roll-off design makes it ideal for transporting helicopters, tanks and other wheeled and tracked military vehicles. Two 110-ton single pedestal twin cranes make it possible to load and unload cargo where shoreside infrastructure is limited or non-existent. A commercial helicopter deck enables emergency, daytime landings. The USNS Benavidez is 950 feet in length, has a beam of 106 feet, and displaces approximately 62,000 long tons. The diesel-powered ship will be able to sustain speeds up to 24 knots.

Ship's name to honor Army hero Benavidez

San Antonio Express News

17 September 2000

The U.S. Navy plans to name a new ship after the late Army Master Sgt. Roy P. Benavidez, a Medal of Honor recipient with deep ties to San Antonio.

The seventh in a class of large, medium speed roll-on/roll-off sealift ships will be named for Benavidez and will be the second Navy vessel named for a Hispanic Texan, U.S. Navy Secretary Richard Danzig said.

"Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez was a true American hero, rising from humble origins in South Texas to become an Army legend," Army Secretary Louis Caldera said.

"Wounded over 40 times as he saved the lives of eight fellow soldiers under heavy fire in Vietnam, he always said he was only doing his duty to his fellow soldiers and to the country he loved," Caldera continued. "The Navy's recognition of his selfless service is truly an appropriate tribute to Master Sgt. Benavidez's memory, and to the ideals of our nation that he epitomized."

To be christened next summer, the USNS Benavidez is to be a non-combatant vessel run by civilian mariners and operated by the U.S. Navy's Military Sealift Command, Washington, D.C.

Built by Litton-Avondale Industries in New Orleans, La., large, medium speed roll-on/roll-off ships, or LMSRs are the Navy's newest class of vessels. They can carry an entire Army task force, including 58 tanks, 48 other tracked vehicles, plus more than 900 trucks for use in combat and humanitarian missions.

Each ship has cargo deck space of more than 380,000 square feet, equivalent to almost eight football fields, and a crew of up to 45 civilians and 50 active-duty military personnel.

The Navy's first LMSR was named after the late Sgt. 1st Class Randall D. Shughart, a Delta Force operative killed in a 1993 battle in Mogadishu, Somalia.

The Navy made history when it launched the guided missile destroyer USS Gonzalez on Oct. 12, 1996, before a crowd of 5,000 at Ingleside Naval Station.

The ship was named for Medal of Honor recipient Alfredo "Freddy" Gonzales, a 21-year-old Marine sergeant from Edinburg who was wounded on Jan. 31, 1968, while protecting fellow GIs during the battle for Hue City, one of the bloodiest campaigns of the Vietnam War. Despite his wounds, Gonzales refused medical treatment and continued supervising an attack, then fell mortally wounded the next day.

"I think it is a great honor," said Benavidez's 28-year-old son, Noel, an El Campo computer network engineer and San Antonio native.

"How many ships are named after soldiers? How many ships are named after an enlisted man?" wondered retired Army Command Sgt. Maj. Benito Guerrero, a longtime Benavidez confidant. "Most of them are named after generals or after presidents."

Danzig described the 950-foot long, 62,000-ton LMSR ships, known as Bob Hope class vessels, as "resolute assets that are always quietly there in the background," capable of providing vital reinforcement worldwide.

The Navy secretary said Benavidez "personified that same spirit throughout his life, and most powerfully during a single action that saved lives in combat."

Benavidez was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross from Gen. William Westmoreland for his heroism in a rescue of Special Forces troops in Cambodia on May 2, 1968. When the full story of his actions became known, the award was upgraded to the Medal of Honor, which Benavidez received from President Reagan in 1981.

A Green Beret, Benavidez was three months into his second tour of Vietnam when a North Vietnamese regiment surrounded a dozen soldiers from his unit during a secret mission to Cambodia authorized by President Johnson.

When he became aware of the situation, then-Staff Sgt. Benavidez thought of three friends trapped in the fire zone and rushed to a helicopter.

"When I got to that 'copter, little did I know we were going to spend six hours in hell," he told the San Antonio Express-News weeks before his death in 1998 at age 63.

Benavidez suffered wounds to the right leg, face and head while charging through heavy enemy fire. He shifted team leaders so they could give cover to the helicopters, then carried the wounded GIs to nearby aircraft.

But that only was the beginning of a vicious fight.

Benavidez retrieved classified documents from a dead team leader, then gathered wounded soldiers from a downed aircraft and set up a defense perimeter. As enemy fire intensified, he called in airstrikes, directed fire from helicopters buzzing over the battlefield and, though badly wounded, administered first aid.

Bleeding from gunshot wounds and hit in the back by grenade fragments, Benavidez was clubbed while leading a second extraction.

In the hand-to-hand fighting that ensued, he suffered wounds to his head and arms before killing his adversary and cutting down two other enemy soldiers as they tried to overtake a helicopter.

The bloodied and exhausted Benavidez then made another trip in search of classified documents, but instead emerged with even more wounded.

Benavidez , a devout Catholic, said he made the sign of the cross so often during the fight his arms "were going like an airplane prop."

"He was a hard-charger, a good soldier, a fighter who never gave up," said retired Army Command Sgt. Maj. Willie Noles, 70, of San Antonio.

"He was a soldier's soldier, there's no doubt about it," Guerrero agreed.

Born in the South Texas German community of Lindenau, Raul Perez Benavidez was a sharecropper's son who barely knew his parents. Salvador and Teresa Benavidez died a year apart, leaving him and a younger brother, Roger, to live with an uncle, Nicholas Benavidez.

The family worked as migrant laborers, toiling in sugar beet and cotton fields from West Texas to Colorado. The young Benavidez spent more time in the field than in school, finishing only the eighth grade, and though he faced discrimination in the 1940s he vowed to master English and his life.

Benavidez found his high school diploma, and upward mobility, in the Army. A stint in airborne school persuaded him to make a career of the service and, he said later, "become a soldier and be the best."

Benavidez died Nov. 29, 1998, at Brooke Army Medical Center. Five days later, more than 1,500 family and friends gave Benavidez one last salute as he was buried in the shade of a live oak tree at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

The man known by Army Special Forces troops everywhere as "Tango Mike Mike" has not been forgotten since that afternoon.

The $14 million Master Sgt. Roy P. Benavidez Special Operations Logistics Complex at Fort Bragg, N.C., was dedicated 13 months ago.

Efforts are under way to erect a statue of Benavidez in El Campo, where his widow, Hilaria "Lala" Benavidez, 66, got word of the Navy's decision Thursday evening.

"It came as a surprise to me to receive a telephone call from Capt. Bill Cullin of the United States Navy to inform me that the secretary of the Navy has decided to name a naval ship after my late husband," she said. "My children and I are truly honored that the Benavidez name will be added to a long list of Navy vessels. Roy would be proud."

Family members already are looking forward to launching the Benavidez, his four grandchildren flanking the VIP section.

"Roy was quite a military man. I think he would be quite proud," said Roger Benavidez, 64, an El Campo real estate broker and former Army National Guard sergeant.

"I think that would be a great thing," Noles said.

"I rarely have heard of these things, that the Navy honors an Army soldier, and I think if my father were here today he would be ecstatic," Noel Benavidez said. "However, I know in my heart that he's grinning from ear to ear."

Roy Benavidez Died at Age 63 on Sunday, 29 November 1998.

By Richard Goldstein,![]() , 4 December

1998

, 4 December

1998

Roy P. Benavidez, a former Green Beret sergeant who received the Medal of Honor from President Ronald Reagan for heroism while wounded in the Vietnam War, then fought to keep the government from cutting off his disability payments, died Nov. 29 at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. He was 63.

Benavidez, who lived in El Campo, Texas, suffered respiratory failure, the hospital said. His right leg was amputated in October because of complications of diabetes.

On the morning of May 2, 1968, Benavidez, a staff sergeant with the Army's Special Forces -- the Green Berets -- heard the cry "get us out of here" over his unit's radio while at his base in Loc Ninh, South Vietnam. He also heard "so much shooting, it sounded like a popcorn machine."

The call for aid came from a 12-man Special Forces team -- 3 Green Berets and 9 Montagnard tribesmen -- that had been ambushed by North Vietnamese troops at a jungle site a few miles inside Cambodia.

Benavidez jumped aboard an evacuation helicopter that flew to the scene. "When I got on that copter, little did I know we were going to spend six hours in hell," he later recalled.

After leaping off the helicopter, Benavidez was shot in the face, head and right leg, but he ran toward his fellow troops, finding four dead and the others wounded.

He dragged survivors aboard the helicopter, but its pilot was killed by enemy fire as he tried to take off, and the helicopter crashed and burned. Benavidez got the troops off the helicopter, and over the next six hours, he organized return fire, called in air strikes, administered morphine and recovered classified documents, although he got shot in the stomach and thigh and hit in the back by grenade fragments. He was bayoneted by a North Vietnamese soldier, whom he killed with a knife. Finally, he shot two enemy soldiers as he dragged the survivors aboard another evacuation helicopter.

When he arrived at Loc Ninh, Benavidez was unable to move or speak. Just as he was about to be placed into a body bag, he spit into a doctor's face to signal that he was still alive and was evacuated for surgery in Saigon.

Benavidez was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1968, but a subsequent recommendation from his commanding officer that he receive the Medal of Honor -- the military's highest award for valor -- could not be approved until a witness confirmed his deeds.

That happened in 1980, when Brian O'Connor, the Green Beret who had radioed the frantic message seeking evacuation, was found in the Fiji Islands. O'Connor told how Benavidez had rescued eight members of his patrol despite being wounded repeatedly.

Reagan presented the Medal of Honor to Benavidez at the Pentagon on Feb. 24, 1981.

Shortly before Memorial Day 1983, Benavidez came forward to say that the Social Security Administration planned to cut off disability payments he had been receiving since he retired from the Army as a master sergeant in 1976. He still had two pieces of shrapnel in his heart and a punctured lung and was in constant pain from his wounds.

The government, as part of a cost-cutting review that had led to the termination of disability assistance to 350,000 people over the preceding two years, had decided that Benavidez could find employment.

"It seems like they want to open up your wounds and pour a little salt in," Benavidez said. "I don't like to use my Medal of Honor for political purposes or personal gain, but if they can do this to me, what will they do to all the others?"

A White House spokesman said that Reagan was "personally concerned" about Benavidez's situation, and 10 days later Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler said the disability reviews would become more "humane and compassionate."

Soon afterward, wearing his Medal of Honor, Benavidez told the House Select Committee on Aging that "the administration that put this medal around my neck is curtailing my benefits."

Benavidez appealed the termination of assistance to an administrative law judge, who ruled in July 1983 that he should continue receiving payments.

When Reagan presented Benavidez with the Medal of Honor, he asked the former sergeant to speak to young people. Benavidez did, visiting schools to stress the need for the education he never had.

Born in south Texas, the son of a sharecopper, Benavidez was orphaned as a youngster. He went to live with an uncle, but dropped out of middle school because he was needed to pick sugar beets and cotton. He joined the Army at 19, went to airborne school, then was injured by a land mine in South Vietnam in 1964. Doctors feared he would never walk again, but he recovered and became a Green Beret. He was on his second Vietnam tour when he carried out his rescue mission.

Benavidez is survived by his wife, Hilaria; a son, Noel; two daughters, Yvette Garcia and Denise Prochazka; a brother, Roger; five stepbrothers, Mike, Eugene, Frank, Nick and Juquin Benavidez; four sisters, Mary Martinez, Lupe Chavez, Helene Vallejo and Eva Campos, and three grandchildren.

Over the years, fellow Texans paid tribute to Benavidez. Several schools, a National Guard armory and an Army Reserve center were named for him.

But he did not regard himself as someone special.

"The real heroes are the ones who gave their lives for their country," Benavidez once said. "I don't like to be called a hero. I just did what I was trained to do."

SAN ANTONIO, Nov. 29 (San Antonio Express-News) Loyalty and a strong sense of duty drove Roy P. Benavidez to save a Special Forces unit cut down in a vicious firefight, even after he was clubbed, stabbed and shot more times than he could recall.

But the proud and feisty Benavidez, a retired Army master sergeant who received the Medal of Honor for his actions in a Cambodian jungle 30 years ago, couldn't fend off a plethora of health problems that had hobbled him in recent months.

Benavidez died Sunday of apparent respiratory failure at Brooke Army Medical Center. He was 63.

"He went as a soldier," said retired Army Master Sgt. Ben Guerrero, who was with family members at Benavidez's side when he died early Sunday afternoon.

"He went the way the good Lord wanted to take him."

Benavidez, a Green Beret and longtime El Campo resident, had been hospitalized in San Antonio since May. Doctors removed part of his right leg in October as complications from diabetes threatened to trigger a fatal infection.

He underwent another surgical procedure at Northeast Methodist Hospital in San Antonio for an undisclosed illness as doctors treated him for diabetes and anemia, among other health woes.

But even as he battled pain from the amputation and tried to regain some of his upper-body strength needed to eventually walk once more, Benavidez remained an icon.

Friends and old soldiers would call his hospital room or send postcards or letters. Months before the amputation, a Memorial Day ceremony was delayed at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery so Benavidez could arrive.

When he did, in a wheelchair, the throng stood in an awestruck silence.

A little more than a week ago, retired Army Lt. Col. Dave Davis met the storied Benavidez.

"We shook hands," said Davis, an aide to U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas.

"Obviously for anybody who served in the military, it was an honor to meet him. He was an inspirational man."

Benavidez received the Medal of Honor from President Reagan in 1981 for saving eight fellow Special Forces soldiers on May 2, 1968.

A North Vietnamese regiment had surrounded a dozen soldiers from his unit during a secret mission in Cambodia that had been authorized by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Three helicopters trying to save the men came under heavy fire and were unable to land.

When he became aware of the situation, Benavidez thought of three friends trapped in the fire zone and rushed to the helicopter.

"When I got on that 'copter, little did I know we were going to spend six hours in hell," he said in an interview earlier this month.

Moments after jumping off his helicopter in a clearing, Benavidez suffered wounds to the right leg, face and head while charging through heavy enemy fire. He repositioned team leaders so they could give cover to the helicopters, then carried the wounded troops to nearby aircraft.

But that was only the beginning of a long and vicious fight.

Benavidez found classified documents from a dead team leader, then gathered wounded troops from a downed aircraft and set up a defense perimeter. As enemy fire intensified, he called in airstrikes, directed fire from helicopter gunships swarming over the battleground and - though himself already gravely wounded - gave first aid to another soldier.

Bleeding from new gunshot wounds to the thigh and abdomen, and hit in the back by grenade fragments, Benavidez was clubbed while leading a second extraction.

In the hand-to-hand fighting that ensued, he suffered wounds to his head and arms before killing his adversary and cutting down two other enemy soldiers as they tried to overtake a helicopter.

The bloodied and exhausted Benavidez then made one last trip, this time looking for classified documents, and brought more wounded in tow to a waiting helicopter.

Throughout the fighting, Benavidez, a devout Catholic, made the sign of the cross so often his arms "were going like an airplane prop." But never gave in to fear.

When told his one-man battle was awesome and extraordinary, he replied: "No, that's duty."

Silence marked his last hours.

Benavidez took a turn for the worse early Sunday and was moved to BAMC's intensive care unit. Guerrero said he had appeared fine the day before.

"We were talking, he ate a bit of lunch and had coffee, and had a piece of roll. And they tell me he ate supper, too," he said. "I don't know. It was just a complete change, the calm before the storm."

Guerrero, speaking on the family's behalf, said Benavidez had suffered breathing problems and didn't respond to those around him.

Still, he received guests.

Fort Sam's commander, Maj. Gen. James Peake, visited Benavidez on Sunday along with Brig. Gen. Harold Timboe and Lt. Gen. Robert Foley. Timboe commands BAMC and Foley, himself a Medal of Honor recipient, oversees the U.S. 5th Army at Fort Sam.

Saying "quitters never win and winners never quit," Benavidez said in his last interview that he wanted to recover so he could continue working as a motivational speaker.

He died at 1:33 p.m.

This story shall the good man teach his son; And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by, From this day to the ending of the world, But we in it shall be remember'd;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile, This day shall gentle his condition: And gentlemen in England now a-bed Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,