Whetstone Mining in the Blackdown Hills

By Andrew Westcott

-- Links to other pages I've written --

Home Page

Radio Stuff

Concert Master

Coxparo

Gin Traps

Grimspound

Rust Electrolysis

National Explosives

Solar Hot Water

Wistmans Wood

Doddi Mines

Rants

Dog Walker

Zombies!

JS Email

Telephone Intercom

Whetstone Mining

Pulsar Zero 2250

Index Of Sub-Sections On This Page:

Introduction

First, A Little Geology

Whetstone Mining

The Last Whetstone Miner

Associated Finds

Investigating The Remains

Further Reading & Links

Introduction To This Project

I have a reasonably healthy interest in industrial archæology, and since moving onto the Blackdown Hills in East Devon, UK, the history of whetstone mining in and around Blackborough has caught my attention. The mines supplied a type of sandstone which proved useful as a whetstone; a high quality scythe stone could be carved from this rock, producing what was known as a Devonshire Batt.

Researching this little-documented mining industry involved a fair number of site visits, and despite the advancing years and the gout I've taken the trouble to do the legwork; I've slipped up, slipped down, got covered in mud, been bruised, cut, scratched, stung and have dragged reluctant companions kicking and screaming through what seemed like miles of brambles, fallen trees and tick-ridden bracken, but I've finally succeeded in visiting most of the whetstone mining sites.

Trying to take meaningful photographs in the middle of a thicket proved to be painful, technically challenging and generally futile, but I have done my best to record some of the remains of the old whetstone mines; the least inept of my photographic attempts appear in the "Investigating The Remains" section further down the page.

While little was recorded about these mines locally, a fair bit of information can be found in accounts written by geologists of the time who visited this region of the Blackdown Hills to examine the geology, made possible by the whetstone miners' tunnels, and who also collected fossils brought out by the miners.

Many of these historic texts are now available on the Internet, but they can take a fair bit of digging to find; where I've quoted from such texts, I have done so word for word to preserve context, rather than trying to reword them for the sake of it and have provided the name of the author and date of publication. Links to available texts are listed at the bottom of the page which generally go into far more detail than I have provided.

As you've quite possibly found this page by doing a web search, I'd like to recommend two excellent texts written in modern times which go into far more detail than I've written here:

Devonshire Batts: The Whetstone Mining industry and community of Blackborough, in the Blackdown Hills

R. G. F. Stanes

The Devonshire Association Volume 125 (1993), pages 71 - 112

Devon's Non-metal Mines

Richard A. Edwards (2011)

Published by Halsgrove

Please drop me an e-mail if you have any comments, or anything to add.

So what's a whetstone?

A whetstone is the name given to an abrasive stone of suitable composition and shape, used to sharpen or 'whet' steel blades.

Beneath the western side of the Blackdown Hills in Devon, United Kingdom, was found a hard, abrasive rock which lent itself superbly to the job of sharpening scythes. Initially, suitable stones would probably have been found in ground disturbed by the uprooting of a tree or perhaps protruding from the banks of streams high up on the hills, but demand led to attempts to mine the stone directly.

A well-used, but surviving Devonshire Batt.

Reproduced with permission: Hemyock Castle

The stone from this area proved to be of exceptional quality and the market for it increased accordingly, creating the economic climate for whetstone mining to flourish here. The finished product was a high quality scythe stone known as a Devonshire Batt, many hundreds of thousands of which were manufactured during the life of the mines and distributed around the south of England and beyond, some even finding their way to Australia.

It is generally accepted that whetstone was mined around the western side of the Blackdown Hills from the 1600s onwards, but by the late 1800s most of the mines had been worked out: "The whetstone pits are now nearly exhausted, and only two or three remain open." - Downes (1880). Reaper-binders were becoming available around this time which were replacing the man & scythe, and in the early 1900s, artificial whetstones made of carborundum started to appear, removing the need to search for further sources of this natural abrasive.

Back to top

First, A Little Geology

The Blackdown Hills in Devon, England consist of a plateau which rises to around 900 feet above sea level in the west, cut through by streams and rivers which have left many deep valleys. In the simplest terms, the hills are composed of a substrate of Triassic mercia mudstone, overlain with a deposit of Cretaceous upper greensand formation of variable thickness but typically ranging between 50 and 100 feet or so; this is finally topped with a thin layer of clay-with-flints, all that remains now of a chalk deposit which once capped the greensand.

The upper greensand layer is responsible for the characteristic flat top of the region, with the edges sometimes exhibiting a steep escarpment; below these often wooded escarpments the ground levels out somewhat and generally gives way to pasture land.

The brown region (dead bracken) indicating the Upper Greensand deposit

It's the upper greensand formation that is of particular interest here, as it is within this deposit that siliceous concretions occur, these being a particular type of hard but porous sandstone consisting of fine grains of silicon compounds in a matrix: "The stone is a quartz-muscovite-tourmaline grit" - Moore (1978). Certain layers of rock within the greensand became highly prized for making Devonshire Batts, the name given to the finished whetstones from this area.

In 1836, Dr. Fitton published the following observation about the beds to be found within the greensand and the thickness of the deposits:

"The following is a sectional list of the beds in one of the principal sithe-stone pits at Punchey Down, which, I was informed, was a fair representative of the whole:

1. Reddish sand rock, extending upwards to the top of the hill.

2. "Fine vein"; Concretions of firmer consistence; the best for sithe-stones. 0' 2" to 1' 0"

(Shells are found in all the strata here, but abound remarkably in this one, and in the "rock" beneath it.)

3. "Top sand rock"; sand with irregular concretions; of no use . 3' 0" to 4' 0"

4. "Gutters"; concretions of stone in 4 or 5 courses, in the sand. 3' 0" to 5' 0"

This bed is that most commonly used for sithe-stones.

5. "Burrows"; stone and sand of the same kind, but used only for building. 2' 0" to 3' 0"

6. "Bottom stone"; a range of concretions, affording excellent sithe-stones. 0' 2" to 0' 6"

(These concretions sometimes extend downwards, even to 5 feet, in the sand.)

7. "Rock sand"; chiefly sand, with fewer concretions; of no use. 4' 0"

8. "Soft vein"; concretions which afford excellent sithe-stones. 0' 2" to 0' 6"

The strata below are not known to the workmen. The total thickness, therefore, of the strata which furnish the material for sithe-stones, including the rejected sand and rubbish, is from 12 to 18 feet, the whole of which is removed in cutting the drifts or galleries."

- Fitton (1836)

The Geological Bench

At locations where a moderately steep escarpment is present, an intermediate shelf or 'bench' can sometimes be seen which occurs at a variable height but typically 10 to 30 metres or so below the top of the plateau, which appears to have been created by differences in erosion resistance.

This intermediate flat zone or 'bench' may appear to be a man-made pathway following the contour and indeed, it is often used as such but it is, in many cases, a natural occurrence. Such benches were often bulldozed to improve the pathway for access to the woodlands by forestry companies making their natural origin less obvious, this being the case with the path through Rhododendron Wood, Kentisbeare, for example.

Simplified cross-section of a Blackdown Hills escarpment

Dumping mine waste over the side of such a bench would eventually increase its width, sometimes dramatically as has happened at Blackborough and North Hill, creating a wide terrace the miners called the 'sandbeds'. The spoil heaps in areas devoid of a natural bench tend to occur at varying levels and therefore don't create a single level region; such an area can be seen east of the road at Hembury Fort.

I'm surprised that no mention has been made of these benches by geologists; the whetstone mines were generally driven into the hill from such a bench so it would seem that the presence of one was an indicator to the miners that raw whetstone may be present and at what level to begin digging their tunnels. The flat platform also of course provided a useful pathway to access the mines with the waste material being conveniently dumped over the side of the escarpment.

Photo 1 |

Photo 2 |

The pair of images above show nice virgin geological benches which haven't been molested by whetstone miners or bulldozers. The bench in photo 1 is fairly wide at this point with the escarpment falling away steeply to the left. The bench in photo 2 runs around the contour for quite some distance, then as the escarpment turns outwards, the bench turns inwards, disappearing into the hillside as can be seen.

These features are in the woods above the hamlet of Beacon (ST 2387 0880) where the escarpment rises excitingly above the few houses there. Sandstone concretions occur in this area and I believe that had their presence been identified by a mining community 300 years ago, this could well have been another Blackborough.

Upper Greensand Fossils

The Upper Greensand (UGS) deposit of the Blackdown hills is presumed to be somewhat over 100 million years old, having been laid down in the mid to late Albian age although some disagree with this and debate is ongoing. In any case, many fossils have been recovered from the deposit over the years, most uncovered by the whetstone miners and sold to visiting geologists, producing a useful additional income. Many of the shells are finely preserved in chalcedony (a form of silica) which has completely replaced the original carbonate; below are examples of some fossils I've recovered.

Fossil 1A large bivalve shell around 7cm across |

Fossil 2An odd tubular fossil, around 6cm long |

Fossil 3Part of a large ammonite fossil |

Fossil 4A concretion containing many fossil gastropod shells |

Fossil 1: a large fossil bivalve shell around 7cm across, originating from the upper greensand. Surface find, collected from the North Hill area.

Fossil 2: an odd tubular fossil of unknown identity, 6cm long and 3cm at the widest point; appears to be made of greensand concretion, so possibly a trace fossil? Collected from a UGS exposure at Blackborough.

Fossil 3: part of a fossil ammonite; I'd estimate this specimen would have been about a foot across if complete. Collected from a UGS exposure at Blackborough.

Fossil 4: a cluster of fossil gastropod shells around 4 inches across, originating from the upper greensand. Surface find, collected from the North Hill area.

Fossil 5Small fossil shell of a predatory gastropod: a murex calcar |

Fossil 6A bivalve fossil, unusually with both halves of the shell still joined |

Fossil 7Fossil bivalve shells |

Fossil 8Some unidentified mollusc shell fossils, possibly a type of oyster |

Fossil 5: a small fossil of what I believe to be a murex calcar, a predatory gastropod, about 15mm across. It is firmly attached to the shells of 2 small bivalve molluscs and I dare not try to remove them in case I damage the specimen.

Fossil 6: A single small fossil bivalve shell about 12mm across, unusually with both halves still joined, suggesting the prehistoric sea in which it lived was unusually calm. In the hi-res photo, there appear to be some sponge spicules among the sand grains within the shell. Collected from a UGS exposure at Blackborough.

Fossil 7: A collection of upper greensand fossil bivalve shells, the largest being about 20mm across. Collected from a UGS exposure at Blackborough.

Fossil 8: Three unidentified fossil mollusc shells, possibly a species of oyster. The flatter opposing valve can be found but tend to be very fragile. Collected from a UGS exposure at Blackborough.

Back to top

Whetstone Mining

Photo 3

A typical whetstone mine entrance

In order to mine for whetstone, the prospectors would start by choosing a suitable location and arranging a lease agreement with the landowner for the right to mine there, or renting an existing mine. A few mines were owned by individuals, others by a consortium of people or families and the remainder owned and run by whetstone dealers, who would have employed labourers to work in their mines. It seems generally accepted that entire families would work in the mines, with perhaps three generations or more working together.

The mining itself would begin by digging a horizontal cut into the escarpment on the side of the hill, producing a trench or gully, the sides of which increased in height as the cut went into the hillside; once there was enough height at the 'face', the tunnelling operation would begin creating what is known as an adit or level (whetstone miners referred to them as pits), dug horizontally into the hillside to allow the sandstone concretions to be found and extracted.

The mines were driven into a sandy material known as Upper Greensand, which although not loose like beach sand, was still quite soft: you could dig at it with a pencil, for example. The miners employed basic hand tools such as picks and shovels to work with, as there were no power tools or explosives used in these mines and there were no trolleys on rails. Despite this, the larger operations were believed to have driven tunnels into the hillside for as much as 200 yards or more.

Photo 3 shows a whetstone miner outside his mine, suggestions being that this may be a Mr Radford rather than Mr Rookley as has been claimed by some sources. Whoever he was, he's shown here shovelling material up onto the sides of the entrance cut, presumably the waste resulting from a whetstone carving session.

Reproduced with permission:

Tiverton Museum of Mid Devon Life

Opinions on whetstone mine depth vary according to the source; Peter Orlando Hutchinson was told that one tunnel extended for 300 yards, but he may have been misinformed; Fitton suggested 300 yards as a maximum, but it seems unlikely that this was typical. Chalk mentioned that some of the galleries were two or three hundred yards in length; other references cite similar tunnel lengths. To add to the confusion, there is reason to believe that some sources confused feet with yards; a tunnel extending for 300 feet for example, seems far more realistic than one extending for 300 yards.

Sinkhole evidence suggests to me that many mines ran for barely 50 yards, this being supported by their relatively small spoil heaps; other mines however have vast spoil heaps associated with them, suggesting they were driven into the hill for a much greater distance.

Charles Vancouver made this observation on the way the mines were worked:

"The manner of working these quarries is by driving a road or level into the side of the hill to the distance of 3 or 400 yards, about 3 feet wide, and five feet and a half high; when the hill has been penetrated to this distance the usual practice is to work out all the loose sandstones within eight or ten yards of the road, leaving pillars at first to support the roof of the mine, but afterwards gradually working them out, and suffering the whole excavation to fall in and fill up after them."

He also commented on the typical size of the sandstone concretions to be found:

"The size of these stones seldom exceeds the size of a horse's head..."

- Vancouver (1808)

It seems fairly clear from this that the miners would begin extracting sandstone concretions from the far end of the mine, gradually working their way back towards the entrance, allowing the worked-out chambers and galleries to collapse behind them once the supporting pillars and timbers had been removed; such chambers could apparently be quite large and must have been hideously unsafe. At first this may seem an odd way to work, but it does allow the exhausted parts of the mine to be backfilled with waste material, meaning that not all of it had to be wheeled all the way back to the entrance to be dumped.

Most of the waste material was sand; basic wooden barrows were used to wheel the waste sand out of the mines and onto the spoil heaps. Considering that a tunnel may have been driven into the hill for a considerable distance, repeatedly wheeling the sand out by hand must have been exhausting work so any work practice which reduced this requirement would no doubt have been very welcome.

As some of the larger mines would have employed more than one labourer pushing a barrow, it was necessary to ensure that barrows could pass each other underground; it has been suggested that the entire tunnel would have been cut wide enough for this, but that would have involved a lot of unnecessary work. It makes sense that widened passing places would have been excavated at certain points, unless they were able to pass at junctions with side-passages which seems more likely and sensible; life as a whetstone miner was difficult enough as it was, they certainly wouldn't have worked any harder than they needed to.

The smaller whetstone mines may well have been worked by a single person, but where several labourers were employed, their duties and skills fell into one of three basic categories, although no doubt there would be some overlapping of skills.

The Miner

He'd work with a pick and shovel underground and was responsible for driving the tunnel forward, locating and extracting the raw whetstone.

The Sand Drivers

These were usually young lads, employed to push the wheelbarrows. They'd load up the sand the miner had loosened and wheel it out of the mine to be dumped down over the spoil heap; they were also responsible for bringing out any pieces of suitable rock for further processing.

The Cutter

He was probably the more skilled of the workers and it was his job to carve whetstones from the rock brought out to him. The whetstones he'd produce would be unfinished and rough-cut at this stage, as the final dressing and 'rubbing' was typically performed away from the mine by the wives and daughters of the families.

Photo 4

Three whetstone workers: the miner, sand driver and cutter

Photo 4 shows three whetstone workers In front of their mine, with the miner on the left posing with his pick and shovel. Centre is a young lad, the 'sand driver', with a barrow of what appear to be rough-cut whetstones with a basing hammer resting on top of them. On the right is the 'cutter', responsible for carving the whetstones, posing with his basing hammer and a whetstone. The familial resemblance between these workers is striking, suggesting that they represent three generations of this particular family.

This is my reproduction of an old damaged photograph of an even older framed photograph hanging on a wall, and according to Rev. Richard Chalk, an inscription on the back of the photo by Jamie M. Foster indicated it was once in the possession of his father, Murray Toogood Foster, Cullompton archaeologist 1867 - 1953.

This photo appears to have been taken professionally, but it is unknown if the original is still extant; for now I've run out of leads looking for it. An annotation suggests it was taken around 1860 - 1870 and may be the only photo of a whetstone mining team to exist.

Reproduced with permission:

South West Heritage Trust (document 3269Z/1)

As the tunnel was driven into the hillside, the sides and roof would have required supporting to prevent them collapsing; this was accomplished using a series of support structures consisting of a pair of timber poles each side of the tunnel with a third tightly wedged across the top of them to brace the roof. The distance between the supporting structures would have depended on how poor the ground was, varying from continuous timbering near the entrance where the sand was loose to perhaps every foot or two in firmer ground, and probably also depended on the courage or foolhardiness of the miner concerned.

The vast amount of timber required would have been heavily competed for, both for use in other mines and for firewood, so it would be reasonable to expect this to have been a substantial expense. This cost had to be delicately balanced against safety, as continuous timbering throughout the mine would have been an expensive luxury; therefore the props tended to be spaced apart somewhat as can be seen in the photos below, to economise on the use of timber. Unfortunately, all too often this allowed a massive fall of sand to occur within the tunnel which could crush the miner, or suffocate him before he could be rescued.

Photo 5 |

Photo 6 |

Photo 5 is a copy of a magic lantern slide by William Weaver Baker. It shows a miner, presumed to be John Rookley, posing for the photograph at the mouth of one of his mines holding an unfinished whetstone in his left hand, and a specialised tool (a basing hammer) used for carving them in his right. (Date unknown.)

Reproduced with permission:

Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, Exeter

Photo 6 shows the interior of a whetstone tunnel, nicely illustrating the timbering used to help secure the walls and roof. Although we seem to be looking at the end of the tunnel, I believe it turned sharply to the left judging by the wheel rut worn in the floor. The similarly styled timbering suggests that these mines were worked by the same person, and indeed may well have been the same tunnel. Date and photographer unknown.

Reproduced with permission:

South West Heritage Trust (document 3269Z/1)

Although the entrances to these tunnels were fairly narrow and low, the miners opened them out significantly in width and height further in as they created the large galleries described earlier as they searched for and extracted the sandstone. The raw whetstone concretions tended to occur in random clumps within a particular layer rather than as a continuous seam, so finding them tended to involve a certain amount of chance and the removal of a lot of sand.

"The strata which afford the whet-stones are about eighty feet below the top of the hill, to which they are parallel. The mines (or 'pits' as they are called) are driven in direct lines into the hill almost horizontally, and in some cases to considerable distances. The stoney masses from which the sithe-stones are cut, are concretions of very irregular figure, imbedded in looser sand, and though very irregular in shape, marks of the stratification of the sand can be traced on their outside.

The masses of which the sithe-stones are made, vary from six to eighteen inches in diameter, and the beds which afford them would form a total thickness of about seven feet, of which about four are fit for that purpose; the looser stone at the top and bottom being employed for building.

The sithe-stone men take from the owners of the soil the privilege of digging for stones, leaving forty yards on each side between the drifts (or 'pits' as they are called). There is no limitation as to depth, and the drifts are commonly pushed to about 300 yards inwards, greater distances not repaying the labour of bringing out the sand."

- Fitton (1836)

The 'cutter' had the job of carving whetstones from the rock brought out to him, and did so using a specialised tool known as a basing hammer. It is well-documented that the sandstone was damp and fairly soft when first brought out so was easy to carve, but later, when exposed to the air it would slowly harden, a phenomenon known as 'seasoning' or 'case hardening'.

"The hardening which seasoning brings to a stone may be attributed to the movement, in solution or suspension, of small amounts of siliceous, calcareous, clay or iron-rich material."

Source: Building stones of Edinburgh.

The cutters may have worked for some considerable time in the same spot; at some sites they chose to work at the entrances to their mine tunnels, meaning they needed to regularly shovel the chipped rock and sand resulting from the carving up over the sides of the entrance cut to keep the way clear; this formed a pronounced ridge on the sides of the cut over time, evidence of which can still be seen in some places. If a cutter chose to work a little away from the entrance, the waste chipped rock and sand was left where it fell and would eventually form a noticeable mound, again, evidence of which can still be seen.

Making The Whetstones

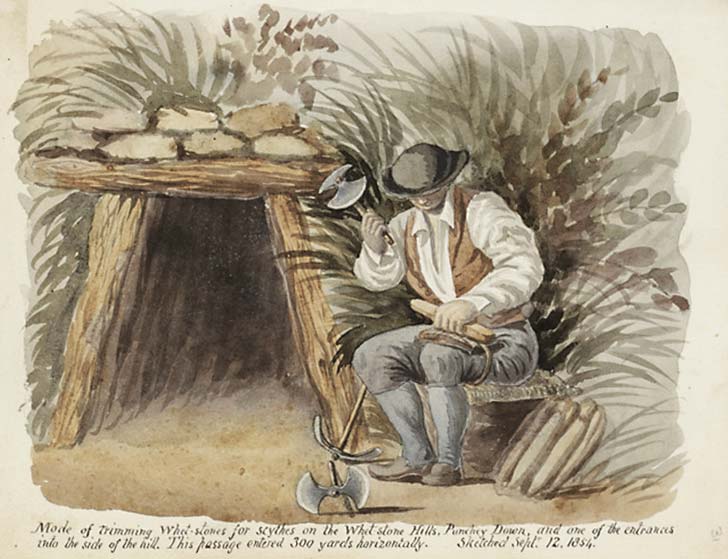

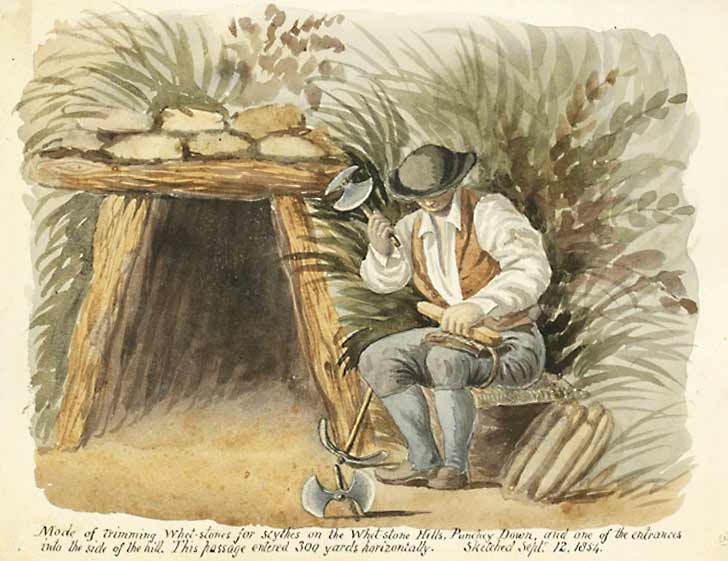

Watercolour painting by Peter Orlando Hutchinson, dated 1854

The text below the painting reads:

"Mode of trimming whetstones for scythes on the Whetstone Hills, Punchey Down, and one of the entrances into the side of the hill. This passage entered 300 yards horizontally. Sketched Sept. 12, 1854."

Reproduced with permission:

South West Heritage Trust & East Devon AONB

The practice of rough-shaping the stones at the mine sensibly reduced the weight of material which needed to be wheeled away in barrows, as the final shaping and dressing of the stones tended to be done elsewhere, often it seems, at the family home, usually by the women of the families. This process was known as "rubbing the stones", and involved more accurately shaping the whetstones and then smoothing their surfaces by rubbing them on a larger piece of sandstone, this part of the process being done in water.

The following text is quoted directly from Dr. Fitton's book published in 1836, and being such a detailed description of whetstone production, it leaves nothing for me to add.

"When first taken out, the stone is greenish and moist, and can be chopped with ease. The tools employed are a sort of axe or adze with a short handle (fig. 2.) called a "basing-hammer" which is ground to a sharp edge. These are made at the adjacent village of Kentisbeare. The other tools are picks without any peculiarity of structure, and "hollowing-shovels" (fig. 1.) for digging the masses of stones out of the sand.

For the purpose of cutting the stones, a vertical post of wood, or 'anvil' is so fixed in the ground as to stand between the knees of the workman, who sits upon a sort of bench built of stone, with some strong pieces of old leather attached as a defence to his left knee.

He first, with the edge of his 'basing-hammer' splits from the blocks upon his knee, long portions approaching to the shape of the sithe-stones; and then cuts or chops them down nearly to the required size, upon the anvil and his knee, just as a carpenter cuts timber with an adze. After thus being rudely shaped, the stones are hewn to the proper dimensions with a large 'hammer', and then rubbed down by women, on a large stone of the same kind; and when dried they are fit for sale.

The stones when finished vary from about ten to twelve inches in length; some have the shape of a portion of an almond, with the ends and sides cut square, and about two inches by one and a half in thickness; others are almost cylindrical, but smaller at each end, with the sides a little curved; the diameter in the middle about two inches.

A good workman can cut out of the blocks about seven dozen of the stones per day. They are sold by the makers chiefly to one merchant at Honiton, who supplies the retail dealers. The prices (in 1825) varied from 2s. per dozen for the finest stones, eleven to twelve inches long, down to 8d. a dozen for the coarsest, ten inches in length."

- Fitton (1836)

It has been suggested that at the period of peak output of the Blackdown whetstone mines, perhaps as many as 10,000 of the sharpening stones were produced by the mines in a week, but this does seem rather a lot as that amounts to half a million stones a year. (Source: Blackdown Hills National Landscape).

Let's analyse this:

we can read that, "At the height of the trade there were about twenty-four pits in working." - Rev. Edwin S. Chalk (1910). For the sake of argument let's assume no-one worked on a Sunday and that the miners worked elsewhere, harvesting perhaps, for around 40 days a year. That would require each mine to produce an average of around 77 scythe stones each working day to reach that half million stones a year.

That's a heck of a lot of whetstones but it does seem possible going by the information given by Dr. Fitton earlier, but I have to agree with Robin Stanes' statement that "even half that figure is considerable." I'm surprised that an industry of this magnitude didn't leave a bigger dent in history, as it now seems to have been all but forgotten.

By the late 1800s most of the readily accessible rock had been mined out despite much reworking of old ground to locate more of the rock. Trying to re-open an old worked-out collapsed mine would have been dangerous and pretty pointless, so new tunnels were dug a short distance away from the old collapsed tunnels and driven in parallel to, above or occasionally below them, to hopefully find new ground that hadn't been fully exploited.

It would seem that the reworking of old ground was already well underway by the end of the 1700s, as we have this from 1793:

"The stratum of sand in which it (concreted sand) is formed, is not confined to any particular depth from the top of the hill; as the workmen are now, in many places, driving fresh pits over those which have been already worked."

- Polwhele (1793).

Evidence of reworking can be seen in many areas and in some locations I've seen as many as six entrance cuts next to each other, indicating that multiple levels were dug parallel to each other to improve the chances of finding virgin ground. In most cases it seems the reworking operations were fairly unsuccessful, as the spoil heaps associated with the later tunnels tend to be small; this suggests the miners either encountered a lot of open space underground due to cutting across old workings or simply found the operation to be uneconomical and the mine subsequently abandoned.

A Risky Business

The ground the mines were driven into was sandy in nature and although easily dug, the tunnels required substantial timbering to prevent them from collapsing; despite careful attention to the supports, it would seem that falls within the mines were commonplace.

The most dangerous work was considered to be digging at the face where timbering was not yet in place, the miners constantly at risk of being killed by many tons of sand 'ruising' in upon them. Surprisingly though, there seem to be very few coroners' reports of deaths caused by collapsing tunnels.

Here's part of the report of an inquest held on 28th of August 1845 as published in the North Devon Journal on Thursday 4 September 1845, on the death of Moses Rookley which sadly illustrates the dangers only too well:

"On Wednesday last the deceased was at work, with his son and daughter, in a pit which he rented of Mr Francis Broom, of Uffculm. About 12 o'clock he was posting up the roof of the pit, about 100 yards from the entrance, when suddenly the earth, sand and stones, fell in on him and covered him entirely as he stood upright; his daughter (aged 20) was knocked down and also covered therewith.

The daughter was not in so far in the pit as the deceased, and the brother, a fine little boy about 12 years of age, who was nearer the entrance of the pit, ran to rescue her, and after half an hour's severe labour, succeeded in removing the earth with his hands from her head and face, so as to prevent suffocation, and then went for further assistance. Whilst he was gone, the daughter called to her father, and asked him if he was buried; the deceased replied, "Yes, I am just dead, and shall never speak to you any more."

"After that some more earth fell down on him, and she heard him groan and subsequently heard him talking to himself (as she expressed it), as though he was praying, but she could not understand what he said. As soon as the little boy (the brother) returned with some other whetstone men, they proceeded to extricate the daughter and then searched for the deceased, and in about an hour found him about five to six feet further in, standing in an upright position, with his arms uplifted, covered with earth and stones, but it took another hour before the body was got out."

Source: GENUKI

The risk of being crushed or suffocated underground wasn't the miners' only problem; whetstone miners were reasonably well paid compared to the local farm workers, earning perhaps triple their income but the extra money came at a cost to health due to exposure to silica dust. The very fine dust which resulted from the shaping of the whetstones and the dust thrown up while digging in the mine itself was known to be particularly problematic, with the health implications well-understood and yet it seems few chose to protect themselves from it. As a result, most of the miners suffered from silicosis to some degree or another.

"A considerable number of men lost their lives through the sand "ruising" in upon them, but many more died before they reached the age of fifty by the "smeech" or fine powder from dressing the stones."

- Chalk (1910)

Silicosis is a disease of the lungs caused by the inhalation of very fine silica dust (known as respirable crystalline silica), and is a well-documented hazard familiar to those who work with stone. Silica is a non-toxic and completely inert mineral found in most rocks, but when microscopic particles are inhaled, they can find their way deep into the lungs and into the alveoli where they cannot be removed by mucociliary action or the body's coughing reflex. As the mineral has a near-zero biosolubility, it cannot be broken down within the body and so persists in the lungs.

The presence of these microscopic sharp fragments of silica within the lungs results in scarring of the lung tissue due to direct trauma and the inflammation response of the body, the combination of which over time reduces the lung's efficiency. This would result in the general breathlessness and persistent cough which was reported among the whetstone miners, with the disability getting more severe as time went on.

Although this condition would be severely debilitating in its later stages, it alone may not necessarily prove fatal; however, when coupled with an attack of tuberculosis which was common at the time, death would be the likely outcome.

"The censuses show that of 151 miners recorded in 5 censuses only 4 were over 60, 19 were over 50, and 118 were under 49. Few seemed to have reached any great age, although many may have left the mines for healthier work as they grew older."

- Stanes (1993)

The whetstone mines were regarded as a dangerous place to work and rightly so, but in my opinion it seems that most of the deaths within the mining community were as a result of lung disorders brought about by the working conditions, rather than accidents within the tunnels as is commonly assumed.

Back to top

The Last Whetstone Miner

John Rookley

Although whetstone mining in the Blackdown Hills was big business for a good 200 years, by the late 1800s mining had all but ceased, as the mines had become worked-out with little new stone to be found despite much reworking of old ground.

By the early 1900s the new artificial carborundum stones had mostly replaced Devonshire Batts as the tool of choice for sharpening blades, and considering that the scythe was by now 'old tech', natural scythe-stones had become pretty much obsolete.

Despite this, a solitary miner, John Rookley, kept digging for the sandstone and produced natural scythe-stones for those still adhering to the old methods of harvest; he finally retired from the mines in 1929 being in his mid to late sixties.

The following is my transcript of a column in the Waverly Dispatch, Volume 34, Number 3, 15 January 1926, which can be seen here: Library Of Virginia.

Old English Industry Now Practically Dead

"The whetstone or scythestone industry, which formerly existed at Blackborough and Sainthill, on the Blackdown range, Devon, England, 800 feet above the sea, is now almost extinct.

Photo 7

Rookley's basing hammer

Founded nearly two hundred years ago, the industry used to provide employment for large numbers of men, women and youths. Now only one worker remains and his attachment is so strong that, despite the loneliness of his calling and the health-impairing nature of the work, he cannot divorce himself from the "dear old hills".

This solitary whetstone craftsman is John Rookley, who, although more than sixty years old, still burrows under the hills and unearths, shapes and dresses the stones which are regarded as unequaled for the sharpening of steel.

The demand for whetstones has diminished astonishingly of late years. Crops are no longer reaped with the scythe; carborundum from the United States is used extensively, and small Welsh stones are compressed for use as sharpeners."

After John Rookley's death, Rev. Edwin S. Chalk obtained his tools from his relatives, and deposited them in Exeter Museum, it is believed some time during the 1930s.

Photo 7 shows John Rookley's basing hammer, reproduced with permission:

Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, Exeter

Where Was John Rookley's Mine?

I believe it is fair to assume that Rookley would have worked several short-lived, short-tunnelled mines during the early 1900s; mining activities over the previous couple of centuries had pretty much depleted the main sources of raw whetstone making a single large mine uneconomical, in addition to which it seems he worked alone and would only be able to manage a small-scale working. Unfortunately no-one in living memory saw his mines in operation, and those who can recall stories told by their parents are now very few in number.

There seems to be some disagreement locally as to where Rookley's mines may have been located, this possibly due to there having been several of them; research suggests that he was living at The Old Manse, Saint Hill in 1931 before later moving to Wales, and up until he retired in 1929 it seems he worked mines in at least two distinct areas, both of which I've dealt with below.

Evidence For North Hill

Evidence suggests that Rookley worked mines in the North Hill area. Recalling the early 1900s, the Rev. Edwin S. Chalk was of the opinion that all the mines around Blackborough were worked out, "for the only pits in operation were on North Hill, beyond Broad Road and thus actually in Broadhembury parish."

As a passing observation, there are references to a James 'Jas' Rookley in material by the Chalks; could this have been a relative of John who also worked mines at that time? Rev. Richard Seymour Chalk wrote, "I remember my father taking Hal Gundry, with my brother and myself to visit Jas Rookley's pit about 1917-8. No one was working at the time, so we did not go inside. The site was on North Hill."

"On a later occasion (perhaps about 1925-6) a friend and I were walking over North Hill when we heard a rhythmical sound, as of a pick-axe, below ground not far from us. We realised it was the last scythe-stone worker still plying his trade. Naturally we were very careful not to walk over his head or anywhere near, knowing how soft was the green-sand soil."

The comment, "the last scythe-stone worker" suggests this was John Rookley.

The above quotes thanks to SWHT (3269Z/1)

North Hill encompasses a large area of mines, stretching continuously for about a mile from Broad Road right around the hill past what was once known as Upcott Pen and onwards east, south of the gliding club airfield, so we have a lot of old workings which could be candidates. However, a close look at the area on an old 25 inch OS map, dated 1892-1914 shows what appear to be only 2 mines in operation, indicated by the red rectangles on the map below; the many other far larger disused mines have only their spoil heaps indicated.

I have provided grid references for both locations in the interest of completeness, but please note that both sites are on private property. I would like to thank Triratna Buddhafield for allowing me to access the site around mine No.1 and to take photographs as part of my ongoing investigations into whetstone mining in the area, but they ask that no-one visits without prior permission. See the Internet Links section near the bottom for contact details.

I believe these two mines must have been in operation at the time of the map's publication, as I see no other reason for the detail: the entrance cuts are marked, as is the extent of what I assume to be the land leased by the miner. Going by the date of the map, these may well be the very last areas to be worked.

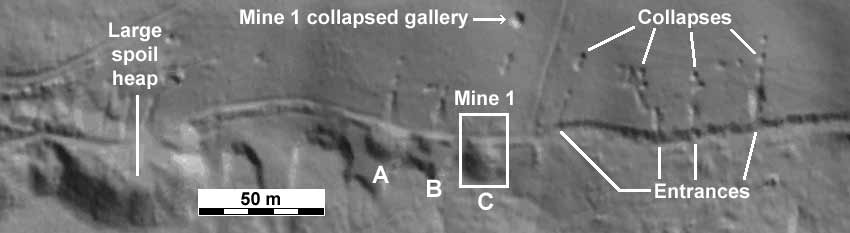

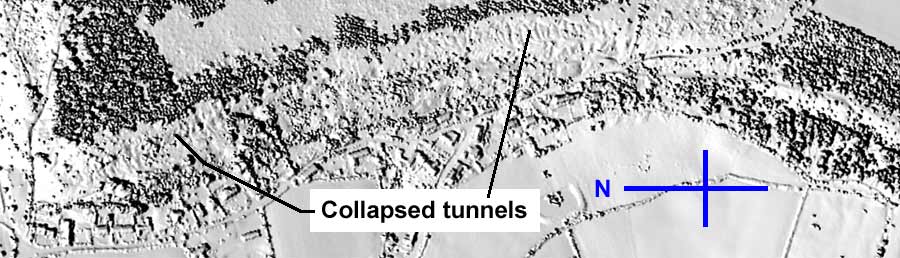

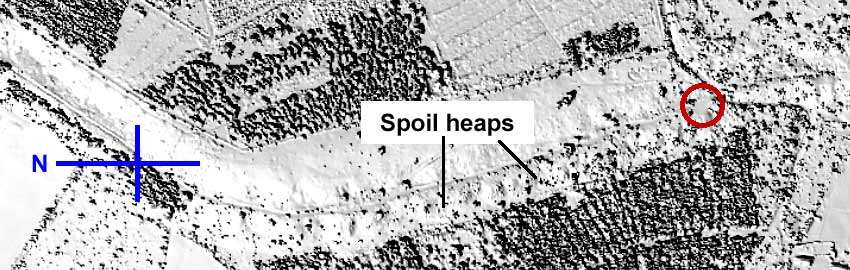

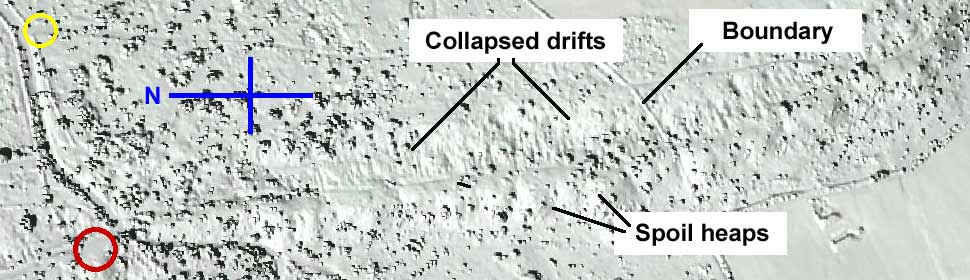

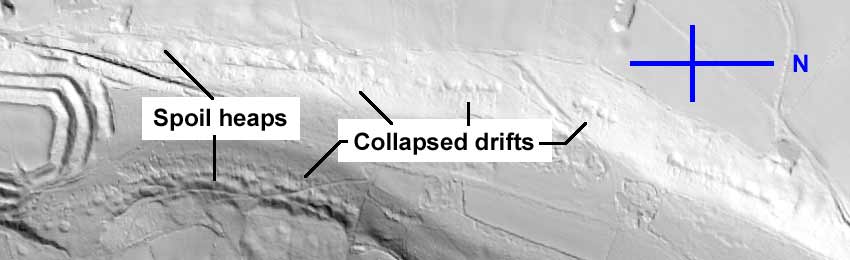

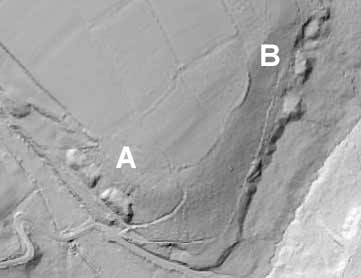

The above LiDAR image shows good evidence of mining activity in this area. The spoil heaps at points A, B & C are small in comparison with most others in the whetstone mining areas, and so are interpreted as short-lived, one-man operations; site 'C' is mine No. 1 on the old map above.

The line the tunnels took underground can be traced by looking at the collapsed ground above them, but note in particular the evidence of collapsed ground on the right side of the image, indicating that 4 small mines operated there. Judging by the short distance the surface collapses extend up the hill, the tunnels were of limited length, around 30 - 40m at best, although oddly there are no discernable spoil heaps associated with these, either on LiDAR or visual examination, but it's possible these were levelled when the track was cut through the area.

Looking again at the LiDAR, note the way in which two of the tunnels appear to turn sharp left around 10 - 15m in, judging by the pattern of collapsed ground: the mine at location B and the second one in of the group of 4 on the right. The tunnel in this photo which was featured earlier also appears to suddenly turn left, going by the wheelbarrow wheel rut in the floor; it's possible this photo could have been taken here, but I have no way of confirming this.

Photo 8 |

Photo 9 |

Photo 10 |

The above photos are 'record shots' to show the spoil heaps for locations A, B & C as they appeared in 2024, the only features which now remain of these smaller mines apart from those important and revealing depressions in the ground above the tunnels, where they have partially collapsed. When the track was bulldozed through the woods, it cut through the remains of all the mine entrances which were once here, meaning there are no entrance cuts remaining to examine.

I suspect this site could be where John Rookley worked, and he may well have been responsible for all the small workings to be seen here, his solitary work perhaps spanning 20 - 30 years at this location, among others.

I saw it written somewhere (exactly where escapes me for the moment) that Rookley regularly pushed his wheelbarrow, laden with whetstones, for around 2 miles from his mine to where he lived in Sainthill, and that is roughly the distance to these mines, which is rather interesting.

Evidence For Rhododendron Wood

Local information suggests Rookley also worked a mine or mines along the Blackborough end of Rhododendron Woods. We have the following information to refer to, thanks to Eric's replies to my enquiries on Social Media:

"My dad Wilf Bird was 99 when he died 9 years ago (as of 2024) so would have been walking to school past there in the 1920s when John was still mining along the Rhododendrons."

"My dad used to walk past his mine on the way to school (now the village hall) from Sainthill daily and would sometimes stop and talk with him. John was a staunch methodist as were all his family. My gran used to take whetstone on a pony and trap to Taunton for John."

"Dad would have walked up from Sainthill (they lived at Prospect House under the hill which later became derelict) to what I have always called the Rhododendrons along the path/bridleway and used to pass his mine along there, and then on down to school which is now the village hall. That is the only location he told me about."

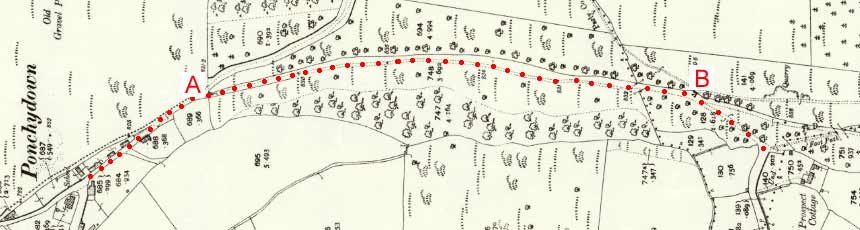

The old map above shows how the young Wilf would have got from Prospect Cottage to school in Ponchydown (as that part of Blackborough was then known), via the miners' path through Rhododendron Wood.

There are now more pathways through the woods than indicated on this old map, presumably tracks made to aid forestry work, but back in Wilf's day, it would appear that the marked path was the only route he could have sensibly taken. The section between points A & B is where his route took him along the track the miners used and where evidence of many old workings can be found, and it would seem that John Rookley worked a mine somewhere between those points. .

The location was extensively mined early on in the area's mining history, I'm guessing in the 1700s, so most of the entrance remains are barely visible, having merged back into the escarpment into which they were dug. At some point in the past, but after the original mines were abandoned, a boundary bank was built along the side of the track at the base of the upper part of the escarpment, and in the process, also across the old disused mine entrance cuts, effectively blocking them as far as wheelbarrow access is concerned.

Photo 11 |

Photo 12 |

Photo 11 shows a section of the old boundary bank, construction date unknown but pre-1900s as it appears on old maps; it was built across the entrances to most of the mines here, so evidently they had long since been abandoned when the bank was built. Evidence of old mine entrance cuts can be seen going into the escarpment here, some just visible in the high resolution image.

Photo 12 shows the entrance cut of a mine which was worked some time after the building of the boundary bank, a gap being dug through it to allow level access to the mine for wheeling barrows in and out.

I have identified several locations between points A & B where mine entrances have been created after the building of the boundary bank, each mine entrance being cut through the bank so evidently post-dating it; any one of these (or possibly all) could have been a site where Rookley worked, although the one shown above is by far the best preserved and so possibly the most recent.

I'll continue to look into this fascinating aspect of local history and will update this section if more evidence comes to light.

Back to top

Associated Finds

It's possible to find various artefacts left behind from the mining activities if you know how and where to look, but do get permission and remember that anything found belongs to the land owner even if there is public access to the area, so ask before you take it home.

This section details the artefacts I've found while examining certain mining areas, or ones that have come to light thanks to people getting in touch with me. It's highly unlikely that any artefacts found around the old mine workings would amount to treasure, but if you find something unusual perhaps contact the local Historic Environment Records officer as it could be of interest from a local history perspective.

Locations of any items I've excavated include a depth below the 'original sand surface'. In all areas there has been an accumulation of rotting organic matter since the miners left which is of a variable thickness but can amount to several inches in places, so depths of finds have been measured once the variable organic layer has been removed to reveal that original sand surface left from the mining activity, this providing a reliable and meaningful reference level.

Unfinished & Broken Whetstones

Bits of broken, unfinished whetstones, although uncommon, are the most likely artefacts to be found around the mines; some whetstone pieces can look rather like random bits of sandstone, but their identity can be confirmed by shape and the presence of tool marks.

Photo 13

Selection of unfinished broken whetstones discarded by the miners

While the cutter was carving scythe stones, he'd produce lot of waste material consisting of sand and rock chippings, analogous perhaps to the debitage of a Mesolithic flint-knapper. This accumulated pile of waste I'll refer to as a 'cutter's pile', and such piles can be found a short distance from the mine entrance or on the sides of the entrance gully, depending on where that particular cutter chose to work.

Occasionally the cutter would accidentally break one of the soft stones he was carving, and no doubt after a bit of colourful language he'd throw the pieces down with the rest of the debris and begin work on the next. Only unfinished broken stones like this are ever found around the mining areas, occurring in various stages of completion but in all cases roughly-shaped, as any complete unbroken stones were of value and were taken away for final dressing, before being sold.

Photo 14

Both halves of a rough-hewn broken whetstone

Photo 14 is unusual in as much that I was able to recover both halves of this broken stone from a cutter's pile, which presumably broke early on in the carving process judging by the very rough shaping. It is uncommon to find both halves of a stone as the bits would have been casually thrown onto the waste pile or even down over the spoil heap, usually to end up some distance apart; in this case, the pieces were found around a metre apart and buried about 15cm under the chippings and sand of the pile which I had carefully excavated; when fitted together this unfinished stone is about 28cm long.

|

|

|

Photo 15 shows a couple of whetstone pieces which have had the surfaces dressed and have bevels on the corners, so I'm assuming they were broken during final dressing. They originated from the site of an old demolished house immediately below the mines in Blackborough. (Thanks to Steve for these.)

Photo 16 shows how the dimensions of the scythe stones vary. Some are almost square in cross-section, while others are rather flatter. It is assumed that only scythe stones where made here, but perhaps the thinner, lighter whetstones where sold for sharpening smaller tools.

Photo 17 shows a pair of scythe stones; a Devonshire Batt almost complete made in the conventional rectangular style but possibly rejected late in the dressing process due to voids in the stone. The other is a cylindrical stone I acquired in the Honiton area, origin unknown. Fitton mentioned that some cylindrical stones were produced, but I've yet to find evidence of a broken part-finished cylindrical stone.

|

|

|

Photo 18 Tool marks can be seen on some of the whetstone pieces if viewed under the right lighting, produced as the stone was worked with a basing hammer; the marks are quite prominent on this example, showing how the cutter 'shaved' material off as he shaped the stone.

Photo 19 An unfinished whetstone showing a large void; voids are quite common in the sandstone from this region and the existence of a void would render the prospective whetstone worthless. A defect such as this would make the stone weak at that point, and it seems that many broke during the carving process because of such cavities or other flaws in the stone.

Photo 20 Occasionally fossils occurr within the sandstone and may be revealed as the whetstone was carved, as was the case with this trace of an ammonite. Such an occurrence was undesirable and would result in the stone being rejected: only a smooth sand surface was acceptable for a Devonshire Batt.

Basing Hammers / Basing Axes

The basing hammer, sometimes referred to as a basing axe, is a highly specialised tool used for carving whetstones from the sandstone concretions. It's interesting to note that according to Stanes (1993), no specialised tool like this seems to have been developed in other whetstone mining areas around the country, making this tool unique to the area and as such, an icon of the whetstone mining industry around the western side of the Blackdown Hills.

We have this account, which describes the tool quite well: (whetstones) "were finally shaped with a strange tool, like a stout hammer with a double head beaten into blades." - Rev. Edwin S. Chalk (1910).

Historic texts suggest there was more than one version of the basing hammer design. Fitton (1836) wrote these comments: "He first, with the edge of his 'basing-hammer' splits from the blocks upon his knee, long portions...". He also wrote in the same paragraph, "...the stones are hewn to the proper dimensions with a large 'hammer'."

This account clearly mentions two different tools for carving the whetstones, and no doubt there were variations on these as the designs evolved over time. It is documented that these tools (and probably all the others the miners used) were made in Kentisbeare, presumably by generations of local blacksmiths who would have done a brisk trade with the miners up on the hill.

An Unused Basing Hammer?

Photo 21 |

Photo 22 |

Photos 21 & 22 were supplied by Jon Snow of Windy Smithy, and show what appears to be a design of basing axe or hammer, used by the miners to carve whetstone. This particular one is quite large measuring around 20cm across; this example, although evidently old, appears to have little or no wear: new old stock perhaps.

This design is difficult to date, but the old photograph of the 3 miners featured earlier shows the cutter holding a basing hammer which appears to be very similar to this one, the date of the photo estimated as between 1860 - 1870.

It is unknown to me exactly where this tool came from but it came to light in the Blackborough area; judging by the type of rust, this had been kept in a dry shed or barn for a very long time and can now be seen in the display board in Blackborough village and could, if the right person reads this, do with a coating of oil to halt the rusting, something I'd be happy to do.

Small Basing Hammer

|

|

This tool was found about 15cm below the original sand surface of a cutter's pile, and what's left of it measures around 14cm at the widest point.

Detail of Rookley's basing hammer.

© RAMM

Although badly corroded now, it looks like it may still have been serviceable in its day, but it seems the cutter thought differently and threw it down with the waste rock, eventually burying it in waste material as he continued to carve whetstones, presumably with a replacement hammer.

Note the broad iron wedge protruding from the underside which would have been driven into the wooden handle to secure it. In this case, the remaining wood around the wedge appears to have been replaced with iron compounds, a kind of fossilisation process if you like. There was no evidence of a wooden handle when it was excavated, so it seems this tool was discarded when the handle broke; surprising really, as the head of the tool would have been the most expensive part by far.

As an observation, this tool appears to be of the same design and size as the one Rookley used, pictured on the right, so can be interpreted as the most recent of the basing hammer designs.

This artefact was carefully treated using electrolytic reduction for 10 days but there is little sound iron left in the blades so it is very fragile; it will probably remain in an anti-rust fluid for the foreseeable future to protect it.

Flat Basing Hammer

|

|

This badly corroded artefact is the head of another basing hammer, of a different design to the previous ones; this one measures around 19cm across and the side view shows the tool is flat, without the slight downward curve seen in the previous examples.

Me taking a soil sample

This artefact was found at a depth of around 25cm under a heap of dumped sand to one side of a mine entrance, with a significant 'halo' of rust-coloured sand surrounding it. It would appear from examining the area that when the mine was first being dug, a few barrow-loads of waste sand were dumped to one side of the entrance before the main spoil heap location was established, and it was in this heap that this axe was found, suggesting it dated from around the time of the opening of the mine and is of considerable age.

This design of basing hammer doesn't appear in any drawings or photographs I'm aware of, suggesting it may date from the early 1800s or before, the badly corroded state seemingly confirming this. However, I did submit a sample of the sand this basing hammer was buried in for testing, and it had a pH of around 4.5, surprisingly acidic; this suggests that the degree of corrosion alone may not be a reliable indicator of age.

This artefact is extremely fragile, and while gently cleaning off the adhering sand and loose rust a piece broke away showing that there is no iron left at all in the blades, they are composed entirely of corrosion products. Gentle magnet tests showed there is some iron remaining in the central part, but that's all. Consequently this artefact isn't suitable for electrolysis treatment and I have attempted to preserve it as it is by soaking to remove chemicals, thoroughly drying it and impregnating it with an anti-rust compound; only time will tell if this is enough to stabilise it.

Many hundreds, perhaps thousands of basing hammers must have been made over the time the mines were operational, and yet I only know of four examples: the two badly corroded ones in my care, the one in the Blackborough notice board and the one in Exeter Museum, so where are they all? No doubt many became worn or damaged and were discarded, to be buried under tons of waste sand; however, many must still survive, perhaps unrecognised and rusting in sheds and barns around the area. For my part, I'm keeping an eye on local antique shops and car boot sales in case any turn up, perhaps misidentified as an odd design of hoe or adze.

If you happen to have, or know the whereabouts of anything that could be a basing hammer or basing axe, please get in touch so I can arrange to have a look, take measurements and photos of it and record it as another surviving example.

Mining Picks

A pick or pickaxe is a tool often associated with mining, and whetstone mining was no exception. The design of pick used in these mines seems to be rather smaller than the two-handed pick usually seen today, and I suspect the smaller size would have made it suitable for one-handed operation should the miner choose to use it that way, and for use in confined spaces.

The broken picks so far recovered seem to have been forged in a similar way: I have been informed that the hole for the handle was likely made by the blacksmith splitting the middle of the bar of iron he was working with, and gradually forging that split into a hole of suitable dimensions for the handle. The artefacts recovered so far show evidence of this method of manufacture.

Pointed Blade of a Miner's Pick

Artefact 3: part of a miner's pick

This is half of a miner's pick measuring 26cm in length, and not only has one end broken off, but it's taken half of the handle hole with it; the way it has broken gives us clues as to how the blacksmith may have formed the tool. Looking at where the iron has broken also suggests this had a vertical blade on the missing half.

I saw part of this protruding from a cutter's pile and after careful excavation was able to withdraw it; unfortunately metal detecting the area didn't recover the other half. This item spent just over a week being carefully treated in an electrolysis cell to recover as much of the artefact as possible, with excellent results.

Vertical Blade of a Miner's Pick

|

|

This is another part of a miner's pick, this time the short vertical blade without the spike; unfortunately the missing part of this wasn't found either but it's reasonable to assume it had a pointed pick at the missing end judging by the fracture detail. This part is about 14cm long and again shows how the blacksmith may have made the tool.

This artefact was discovered at a depth of around 20cm below the original sand surface, on the top of the bank on one side of an entrance's access gully. The tool's location suggests that the miner broke the tool and threw it up over the side and over time it got buried by waste thrown over it as the access gully was being kept clear.

This tool was treated for a week in an electrolysis cell with good success, as it had a lot of metal remaining; the handle cavity was filled with sand when it was excavated, with no trace of wood.

Miscellaneous Finds

This section deals with any finds, metallic or otherwise, which don't fall into the above categories.

Possible Forged Nail Or Wedge

|

|

Not the most exciting of artefacts perhaps, but this square-sectioned spike was left behind by the miners and was found around 8cm below the sand surface just outside the entrance to one of the mines: the 'sandbeds' as the sand-covered access track was called by the miners. This component has no head, is also curved slightly and rather than tapering to a point, thins only in one plane, leaving a chisel-like tip; this suggests the possibility that this may have been a small wedge for some purpose.

Forged iron nails were made by the local blacksmith and would have been used in most of the wooden structures made by the miners, such as sheds and doors to the mines, and iron wedges would have been used to secure wooden handles to iron tools. It is unknown what this particular artefact was used for as there was no evidence of wood associated with it, but it was evidently dropped or discarded and ended up embedded in the trackway prior to the mines being abandoned.

This small artefact was treated in the electrochemical cell for 5 days at a very low current, and cleaned up reasonably well considering how corroded it was.

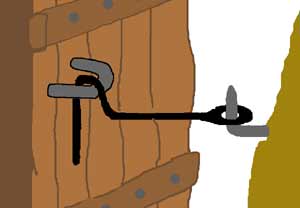

Retaining Latch

|

|

This iron component was dug out from the flat-topped area of a spoil heap from a depth of around 15cm below the original sand surface so was 100% contemporary with the mining activity. It was buried almost vertically with the flattened end upwards, which may have been because it was originally discarded or lost down over the slope of the spoil heap, to be later buried as further waste was dumped over it, gradually increasing the extent of the spoil heap past the place where the artefact was deposited.

Possible use?

My first thought was that this could have been a field gate latch and nothing to do with the mines, but the flattened end with the hole is in the wrong plane for that, and in any case such a gate latch would usually have been formed by bending the iron around onto itself, forming a loop which would have been stapled to the gate.

Consider this: "Tunnels in use had, latterly, carefully locked doors." - Stanes (1993). These mine doors would have needed a way to keep them open during use, as would the doors of any sheds the miners built, so perhaps this was used to secure them in the open position. The flattened end could have been slipped over a small bent spike driven into a wooden stake near the entrance, and the hook engaged with a loop on the door itself, very similar to the way doors are held open now.

This artefact was treated using electrolysis but didn't respond as well as hoped, as there appeared to be no conversion of the black rust layer in this case; in some areas this layer became detached, exposing the iron core but the original dimensions can still be determined. As with all the recovered iron artefacts here, this will now be kept coated in an anti-rust compound.

Back to top

Investigating The Remains

First, A Bit Of A Warning

As the miners searched for the raw whetstone, they excavated large galleries underground and once those areas became exhausted, the timber props were removed for re-use which allowed that part of the mine to partially collapse. In some places the collapsing voids have worked their way to the surface resulting in depressions and sinkholes in the ground above the mines.

Most mine collapses happened a long time ago and are probably stable; however, many cavities must still exist below ground and some are still in the process of collapsing, resulting in new sinkholes appearing. It's wise to be careful when exploring these areas and to take someone with you because if you were to slip into one of these cavities, you may not be able to get out unaided and no-one would know you were there.

Photo 23 |

Photo 24 |

Photo 25 |

Photo 23 shows a hole open to the surface which was around a foot or so across and could pass for a badger hole, but when I stuck my head down it, I could see a cavity which appeared to be large enough to bury a small car, end up. The only reason the cavity wasn't fully open at the surface was because of the network of tree roots, which were supporting the soil and leaves: a perfect trap for the unwary.

Photo 24 shows a large sinkhole, measuring around 10 feet across and a good 6 feet deep. Sinkholes like these occur in lines following the mine tunnels beneath, the result of collapsed galleries 80 - 100 feet below the surface; they are generally historic and are probably stable but you can't be sure, so areas like this are best treated with caution.

Photo 25 shows a larger area of sunken ground, evidence of the large mine cavities that once existed below.

The General Locality, And What To Look For

As far as I can determine, almost all of the whetstone mining occurred on the western escarpment of the Blackdown hills in an area stretching from the eastern side of Blackborough Common near Bodmiscombe continuously around the hill past Sainthill to North Hill and beyond, and intermittently around Broadhembury as far as the Hembury Fort spur, both sides of which were mined; the approximate areas of mining currently known to me are marked on the map in red.

It has been reported that mining activity around this region was once so intense that the spoil heaps were visible from the Cullompton to Honiton road and the Exeter to Bristol railway as an almost continuous white line high up on the hill, and were "suggestive of a railway embankment" - Downes (1880). Looking at the mining locations on the map, the spoil heaps would certainly have been visible from the west and did, it is written, attract visitors who were keen to find out what was going on.

Spoil heap material

These spoil heaps are by far the most obvious evidence of whetstone mining to be found now. The material they are composed of is a light-brown rusty colour when freshly exposed due to the iron compounds contained within, but when open to the elements over an extended period of time, the colour gets washed out, leaving a grey sandy material which sparkles slightly in the sunlight due to the tiny quartz crystals present; such spoil material would certainly have stood out on the hillside. These days the spoil heaps are covered with a good layer of dead organic matter, undergrowth, or both, meaning that the material they are composed of cannot readily be seen without a bit of work.

The tunnels cut into the greensand required extensive timbering to prevent them from collapsing but when a mine was abandoned, the timbering (a valuable resource) was removed for re-use and the tunnel allowed to fall into disrepair. "No open entrance to the mines survives, they were deliberately collapsed according to local opinion." - Stanes (1993).

The idea of intentional collapse could have arisen due to the methodical removal of the timbering, making the collapses seem intentional although it is possible that the collapsing of a tunnel entrance was hastened to make it safe, preventing accidents befalling curious children, for example.

Although the tunnel entrances have long since collapsed, in most areas the lead-in cuts for the tunnel entrances can still be made out although they are in a generally poor condition and some are now represented by nothing more than slight depressions in the ground.

Photo 3 (from earlier) |

Photo 26 |

These lead-in cuts are important features of the mine remains and pinpoint where the mine entrance was; trying to explain what I mean by a 'cut' isn't easy, so I've prepared these two photos to illustrate the feature, by way of a 'before' and 'after' illustration.

Photo 3 is repeated again here as this particular photo nicely shows the horizontal cut going into the rising ground leading to the tunnel entrance proper, behind the miner, typical of these mine entrances.

Reproduced with permission:

Tiverton Museum of Mid Devon Life

Photo 26 shows a mine entrance where the cut is all that remains, partially obscured by material which has fallen in over the sides, and where the ground immediately above the entrance has slumped down when the supports were removed. Allowing for the ravages of time, there is a striking similarity between these entrances so it's possible that these are one and the same, although I have no way to confirm that.

About The LiDAR Images Used Here

The following sections use images generated using LiDAR data, gathered by firing a laser at the ground from an aircraft, and measuring the time taken for the light to return from the target to determine the height of the surface at that point. This technology has proved to be invaluable to archaeologists, and has proved useful in my research into these old mines.

LiDAR data © Environment Agency copyright and/or database right 2022. All rights reserved.

Screenshots thanks to the National Library of Scotland

Mining Above Blackborough

Directions & Access

The best way to access the mines in this area is to park by the churchyard in Blackborough at grid reference ST 0943 0923, but be aware that this isn't a car park as such, so park considerately. Go up the track on the opposite side of the road which is a public right of way, then taking the fork to the right to access the mines above the village. If you carry on up the hill instead, forking left by the wooden fence, this will take you past more workings to the north and east of the common, but be aware that although the track seems to get a lot of use, it's not a right of way and therefore you should get permission before entering.

Details

Blackborough is generally accepted as being where whetstone mining began in this area, the miners and their families having lived in the houses in this hamlet once known as Ponchy Down. This was a busy mining area and the workings continue on around the common in a clockwise direction from the village for some distance.

Photo 27 |

Photo 28 |

Photo 27 shows a particularly large spoil heap above Blackborough. There are several of this size up here, with the mature beech tree giving some sense of scale; considering all this material was dumped over the side using just a barrow, the amount of work this represents is mind-boggling.

Photo 28 shows a single lead-in cut for a mine entrance, the sides of which are easily visible; the tunnel proper would have entered the rising escarpment to the rear.

Mining In Rhododendron Wood

Directions & Access

The best way to access Rhododendron Wood is probably to park in the small car park (circled red on the map below) at grid reference ST 0955 0686, which allows easy access to the bridle path through the woods which goes all the way through to Blackborough. The first half of the woods is owned by the Woodland Trust, the other half is in private ownership.

Details

There is good evidence of a geological bench here, but the track has been bulldozed to allow easy access for machinery and now provides a pleasant, level woodland walk, although in some places the track has been cut several feet lower than the original surface, leaving tunnel entrances and spoil heaps sitting quite a bit higher than the more recently cut track. The remains to be seen here are generally in a very overgrown condition so are difficult to examine, although a few good examples of the old tunnel entrances can be seen.

Photo 29 |

Photo 30 |

Photo 29 shows one of the spoil heaps, this one being fairly large. Working seemed a bit sporadic along this path, as many of the spoil heaps are fairly small compared to those in other areas, suggesting less of the whetstone rock was to be found here.

Photo 30 shows the remains of a pair of tunnel entrances in reasonable condition, the sides of the cuts illustrating the presence of a level bench at this point. The entrances would have entered the escarpment near where I was standing.

Mining Around North Hill

Directions & Access

North Hill is the name given to the large headland north of Broadhembury, most of which has evidence of having been mined. The best way to access a particularly interesting part of this area is to park in the small car park circled in yellow at grid reference ST 0971 0690, or park in the Rhododendron Wood car park (circled red) and walk a short distance up the road to this car park and take the bridle path going roughly south.

This area of woodland is bisected by a boundary hedge; the first northern section being listed as common land, implying you can go off the path to examine the workings lower down in the wood. The southern half is in private ownership, so stick to the path in this section. The boundary between the two consists of the bridle path gate set in an old hedge bank which can be seen going down the hill through the woods, making the boundary obvious.

The bridle path takes you above the workings in the northern end but several areas of collapsed ground are visible from the path. The path continues on through the boundary gate, finally going down through the mining remains in the southern end where they can be seen without leaving the path. The path finally climbs again and exits the woods onto the airfield of the Devon & Somerset Gliding Club.

Details

This area of woodland is fairly overgrown and it seems no-one has used the old miners' track since the mining ceased; the remains of many tunnels and spoil heaps can be seen here which seem to be generally well-preserved and don't appear to have been disturbed since the mining days. Some of the best preserved entrance cuts can be found near the boundary bank, but are difficult to see due to a good crop of bracken and brambles which cover them.

Throughout this region you can clearly see the almost continuous line of mines and spoil heaps which roughly follow the 260m contour, but later reworking at the southern end has confused the area somewhat as many of the later mines had been opened above the old, and the spoil heaps from these, although not as big, tend to spill over the older workings. The creation of the bridle path in this area has also damaged evidence of some of the higher level entrances.

Photo 31 |

Photo 32 |

Photo 33 |

Photo 34 |

Photos 31 & 32 are shots along the 'sandbeds', the mine entrances being to the right and the spoil material dumped down over to the left. Although now pleasantly overgrown, when the mines were active, the dumped sand all around the hillside had no vegetation growing on it and was highly visible at a distance from the west.

Photos 33 & 34 show where two of the many adit entrances were, with the left-hand one being particularly well preserved. The entrances proper would have been at the far end of the cuts, but once the timber supports were removed, the ground immediately above the tunnel entrances slumped down into the cut, effectively closing off the mine.

Mines Around Hembury Fort

Directions & Access

For this area, park in the car park at grid reference ST 1126 0352. There is an information board there with a route marked out, and by following this you can see some spoil heaps and if you look carefully, evidence of collapsed adit entrances can be seen; this all being to the west of the road. Cross the road and go down through the woods to access the mining area to the east of the road, where the mining remains are much more in evidence; as far as I know there isn't public access to this part, but people do walk their dogs down there and I haven't heard of anyone getting shot as yet.

Details

Looking at the LiDAR map above, evidence of quite a bit of mining activity can be seen on both sides of the road with a few smaller workings continuing on the western side towards the right of the image.

Commenting on the line of spoil heaps visible: "More interrupted lines may also be seen in the escarpment facing Broadhembury, and the continuance of the same concretions may be traced by the refuse heaps in several other places." - De La Beche (1839). This presumably refers in part to the workings to the west of the road at Hembury Fort, and suggests many of the mining areas were worked concurrently.

Workings east of the road

This area shows evidence of a considerable number of workings, with many collapsed mine entrances indicating they worked the ground at two levels here; there appears to be no indication of a geological bench at this location and the slope of the ground is far gentler than the escarpment on the other side of the road.

Photo 35 |

Photo 36 |

Photo 35 shows a shot through the woods, with several spoil heaps in evidence to the left, with the tunnels entering the hill on the right. There is a minimal accumulation of organic material in this area, meaning that in some places the spoil heap material can be seen on the surface, without the need to remove the moss and rotting organic matter first.

Photo 36 shows evidence of a collapsed mine entrance, with just the lead-in cut in the hillside remaining; this is typical of the condition that most of the whetstone mine entrances are in now.

Workings west of the road